Collins, Andrew. The First Female Pharaoh: Sobekneferu, Goddess of the Seven Stars. Rochester, Vermont: Bear & Company, 2023. $26.00

In Andrew Collins’ book The First Female Pharaoh, Collins attempts to answer several questions about “the first woman to wear the crowns both of Upper Egypt and of Lower Egypt.” The questions include those that ask who she was, where she came from, what her goals were, and what became of her after she died. Of course, Collins also tackles the questions surrounding her death: was she killed or did she take her own life? But, perhaps a bit surprisingly, he completes the book by taking a look at her legacy in modern pop culture such as in film, which, I found delightfully unexpected.

Collins is no first time author, and has written at least a half-dozen other titles for Inner Traditions and Bear & Company—none of which I recommend. This includes Denisovan Origins, which was co-authored with Gregory L. Little. I’ve read completely or partially many of these and wrote a critical review of Denisovan Origins, pointing out some of its larger academic flaws.

However, I think I have to say I enjoyed reading The First Female Pharaoh. I even found it educational. First, I should point out that this book was sent to me by the publisher for review but I fully expected to find significant flaws in the scholarship. Admittedly, I am not an Egyptologist, but as an archaeologist, my direct experiences include prehistoric and historic North America, rock art, and the Neolithic of the Mediterranean region. While not an expert, I am quite familiar with Egyptian archaeology and the periods pertinent to the book.

For the most part, Collins seems intent on collating academic and some esoteric sources in order to piece together a detailed timeline of Sobekneferu’s life and death. And this, I think, is a good thing. The academic sources range from data and observations beginning in the 19th century through the 20th and into the 21st, citing authors like William Petrie, Percy Newberry, Karl R. Lepsius, Labib Habachi, R.O. Faulkner, Deiter Arnold, and Kara Cooney. He also draws from sources like Menetho, Herodotus, and Plinys Younger and Elder, as well as esoteric sources like Genesis and other books of the Pentateuch. The resulting narrative, for the most part, comes across very credible and informative. The sources are cited with footnotes which lead to chapter notes at the end of the book. Behind the chapter notes is the bibliography, both of which I found helpful and logically organized.

The book itself is organized into eight parts.

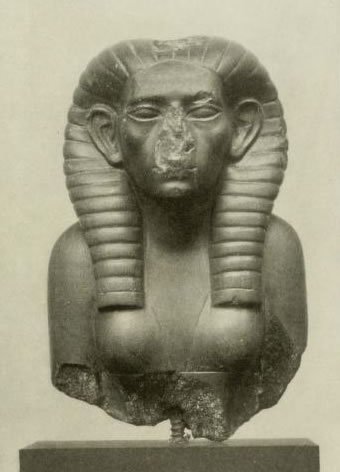

“Discovering Sobekneferu” is the first part, and this is where Collins explores much of the archaeology and lays the foundation of what’s known to date about her. The second part, “Road to Destiny,” explores Sobekneferu’s connection to Canaan and the circumstances and qualities that come together to provide an opportunity for her to rule.

“Seeds of Destruction” begins part three of the book with a discussion of Neferuptah, Sobekneferu’s sister and what’s known about her family: her Father, Amenemhat III and her brother, Amenemhat IV. Collins also explores a connection to that more famous female Egyptian pharaoh, Hatshepsut, which I found interesting. Part four explores the story of Nitocris as told through Herodotus and Manetho and Collins attempts to reconcile their incongruities. Manetho, of course, had his share of inaccuracies, but Herodotus is a source to be taken with many grains of salt. Still, I think Collins manages to contextualize these two sources well enough to tease out some possibilities, which he shares. Is he right? Even Collins admits there is a fair bit of speculation and uncertainty in Sobekneferu’s narrative.

Part five of the book is the part I found the most irrelevant. This part is titled “Faith” and is all about the Biblical story of Joseph. On the one hand, Collins notes that it isn’t his intent to “confirm the historical validity of characters” in the Bible, but he makes some not insignificant connections between the Hyksos and the Israelites of the Bible’s Exodus. There are many reasons why this conflation is both unnecessary and wrong, though I think a discussion of it might detract from the overall review of the book. Suffice to say the only real connection between the Hyksos and the Biblical Israelites is that they’re both of Canaanite origin. I think The First Female Pharaoh would have been better with this chapter left out.

The next two sections, “Two Lands” and “Ancestors” were thoroughly enjoyable as there was good discussion of archaeological sites like the pyramid of Amenemhat III at Hawara, and the Labyrinth that accompanies it. It’s here that I mistakenly thought Collins misspelled the word “mummies” where he writes “’[i]n the same cemetery Petrie found a number of crocodile dummies…” In spite of the fact that Collins continues his description of Petrie’s find that included “bundles of reed and grass” my mind quickly associated an Egyptian cemetery with “mummies” but I followed the citation to Petrie 1889, p. 10 and there was his description of crocodile dummies. Fascinating.

To that end, I followed up a handful of citations here and there and they were unexpectedly accurate. “Unexpected” because of my past experience with Collins’ work.

My chief complaint of The First Female Pharaoh was that it didn’t need the esoteric inclusion of Biblical narrative, though I can see how this might be appreciated by the thousands of “Biblical archaeology” readers. I also lean a little more to Manetho than Herodotus than Collins on the Nitocris story, though they’re both not without problem. However, among the features of the book I found to be positive was the method of citing sources using footnotes to chapter notes which then referred to a bibliography. This eliminates the business dozens of distracting parentheses on each page. Overall, this was a well-illustrated, well-cited book that was also well-organized. Collins managed the menagerie of sources well as he put them together in a single narrative.

To close this review, I have a few hopes:

1) that Andrew Collins continues turn away from the darkside of speculative archaeology and prehistory and writes more genuine archaeological work. I liked The First Female Pharaoh in spite of some of the speculation that still shows up. In fact, I’d go so far as to say much if not all the speculation in this book where it happened was warranted mostly because Collins admitted it is speculation. Several times in this book, Collins admits where he’s speculating and, in some cases, he offers some alternative possibilities.

2) I hope my lack of expertise in Egyptian history and archaeology, along with my excitement that Collins perhaps wrote a legitimate work of archaeological and historic value, did not cause me to overlook something I should have been more critical about. There is so little information available in a single text for Sobekneferu that a book like this becomes useful.

3) I hope that Inner Traditions and Bear & Company continue to publish serious works that avoid sensationalism and overs-peculation. The world has enough “ancient aliens,” “nephilim skulls,” and “Atlantis” retellings than it needs. And $100 academic tomes written in dry narrative aren’t read by anyone not writing a dissertation or thesis.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.