I’ve been wanting to write a good overview of this relatively modern hoax for a while, so what follows is a detailed summary of what the KRS is, who some of the personalities surrounding it are, and why it’s probably a 19th century hoax.

What is it?

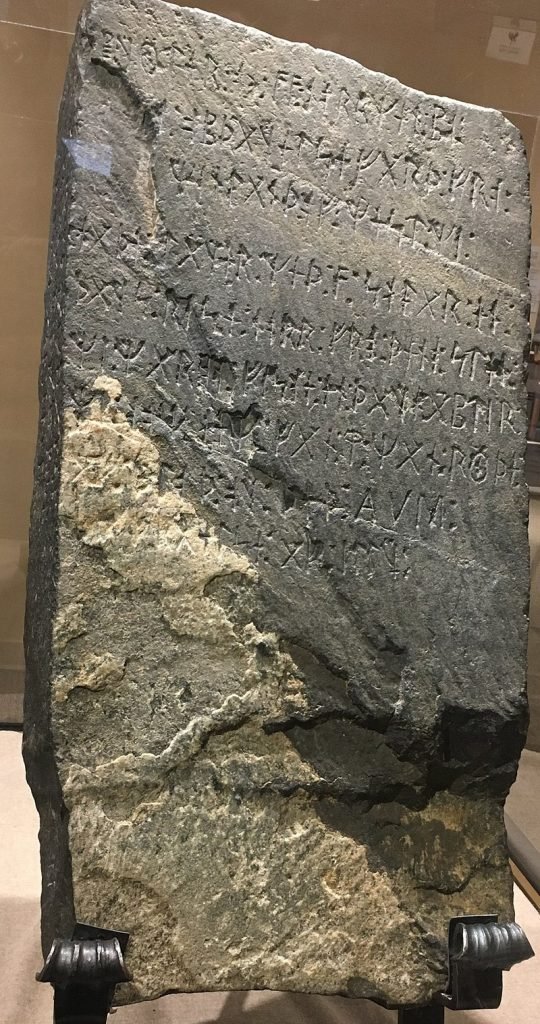

The Kensington Rune Stone (KRS), is a large, flat chunk of greywacke incised with runes. Greywacke is a type of sandstone that essentially has more than 15% clay, often giving it a grey color, and angular, poorly sorted minerals. Non-greywacke sandstones typically have rounded and sorted mineral compositions.

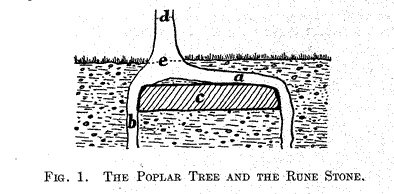

Supposedly discovered by Swedish immigrant Olof Ohman in a farm field in 1898, the stone is 76 cm tall, 41 cm wide, and 15 cm thick. And it weighs about 200 pounds. Ohman claimed he located it under a popular tree that he was uprooting while clearing land on his farm. When he saw the markings, he said he thought he might have found an “Indian almanac.”

In 1911, Ohman sold the stone for $10 to Hjalmar Holand who insisted on the stone’s authenticity as a rune stone created by Norse men in antiquity. And whenever the stone was criticized for linguistic, translation, or textual problems, Holand leaned heavily on the stone’s geological, historical, and anecdotal evidences. All of which were ephemeral and difficult to qualify.

When and Where, Now?

In July of 1909, Olof Ohman, the farmer who found it, and his Norwegian-American neighbor, Nils Flaten, both wrote affidavits about the discovery. A full eleven years after the fact. Both attested that it was found under the roots of a tree and included details of the tree’s location, its size, and the day it was found.

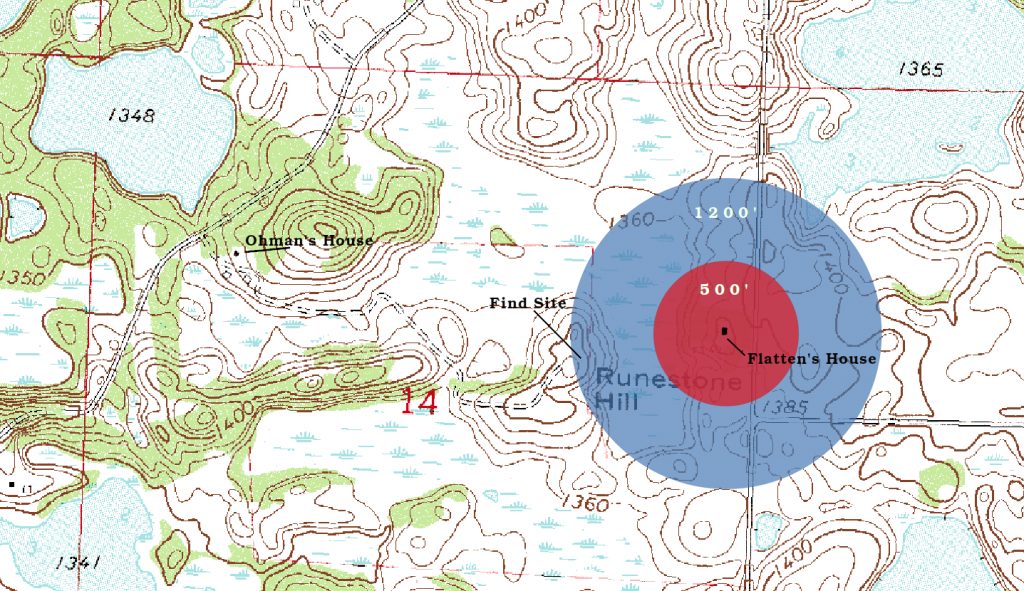

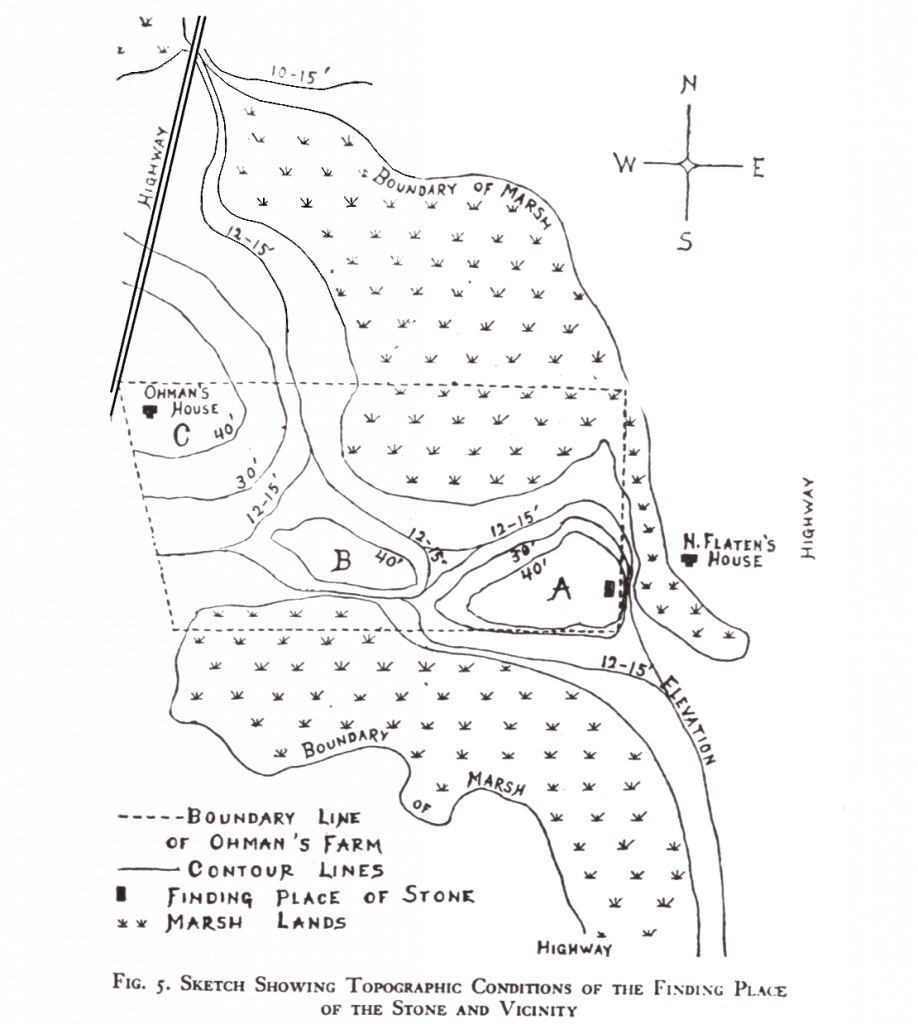

Olof Ohman’s affidavit. Ohman stated that he immigrated to the U.S. from Sweden in 1881 and established his farm in 1891. He continued by stating that, in August of 1898 he was clearing trees and brush about 500 feet west of his neighbor’s house (Flaten) when he removed a 10-inch tree that had a large stone within its roots. Stories conflict, depending on when they were told and by whom, but Ohman’s affidavit indicates he noticed the stone was “inscribed with characters, to me unintelligible. And he goes into much detail about which root was wrapped around which part of the stone and finishes by saying he immediately called his neighbor Nils Flatten who came over that same day to see the stone.

Nils Flatten’s affidavit. Flaten’s words almost directly mirror Ohman’s with regard to the date, the activity, the location, the stone’s dimensions, that it was “covered with strange characters” that “presented [as] very ancient and weathered…”

But the location that Ohman supposedly found the stone wasn’t 500 feet from Flatten’s house. It couldn’t have been, since 500 feet west of Flatten’s home was a swamp. On Flatten’s own land. The knoll where the tree was supposedly grubbed was about 1200 feet west of Flatten’s home.

The MHS Report. In 1910, the Minnesota Historical Society issued a report about the stone which stated it was found on November 8, 1898. Not “one day in August” as stated in the Ohman and Flatten affidavits. Interestingly enough, the MHS report didn’t even include the affidavits notarized by R. J. Rasmusson of Douglas County on July 20, 1909.

Sold for 10 Dollars. In 1911, Ohman sold the KRS to Hjalmar Holand for $10, though he presented it to Holand in August of 1907. Once in his possession, Holand insisted that the KSR was genuine in spite of any and all criticism. During the years Holand possessed stone, and whenever critics and skeptics would bring up the linguistic and textual evidence that questioned the stone’s authenticity, he’d move the conversation to the more ephemeral and hard to quantify attributes of the stone: its geologic, historic, and anecdotal qualities.

The Markings

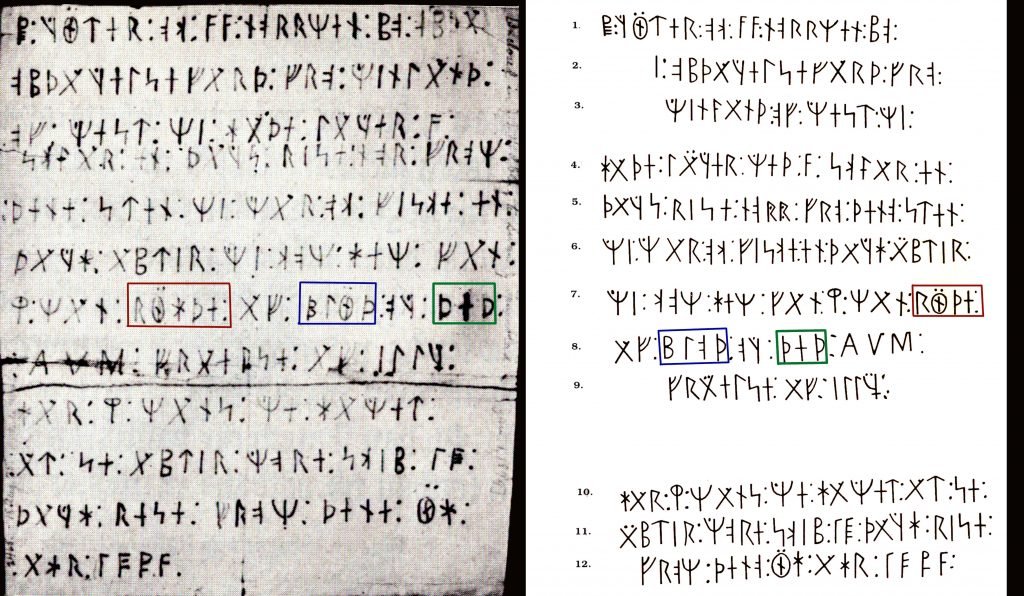

The markings are nine lines of runic text on the face and three lines on the edge. It transliterates to a language understood by most modern Scandinavians and is very close to 19th century Swedish. Essentially, the text translates to:

“Eight Geats and twenty-two Norwegians on an exploration journey from Vinland to the west. We had camp by two skerries one day’s journey north from this stone. We were [out] to fish one day. After we came home [we] found ten men red of blood and dead. AVM (Ave Virgo Maria) save [us] from evil.”

“[We] have ten men by the sea to look after our ships, fourteen days’ travel from this island. [In the] year 1362.”

Translation of the KRS copied directly from Wikipedia.

Problems with the Stone

Aside from the obvious problems about when the KRS was found (was it in August of 1898 or November 8, 1898?), and where it was dug out of the ground from (500 feet from Flatten’s home on Flatten’s own land or 1200 feet from his home on Ohman’s land?), there are a few other problems with the stone itself. Not the least of these is the overall patina of the stone, which is inconsistent with the inscription.

The letters are much lighter than the stone’s surface, which would be consistent with a fresh inscription. Inscribed sandstone stelae or rune stones that are buried for 600 years would have a more even patina between the surface and within the incising. In addition, the incising itself appeared fresh to initial observers. In the MHS report, Winchell wrote:

The first impression derived from the inscriptions is that it is of recent date, and not 548 years old. The edges and angle s of the chiseling are sharp, and show no apparent alteration by weathering.

Professor N.H. Winchell, Minnesota Historical Society Report, Vol. XV, p. 234, 1910.

These problems are all easily explained away, of course: Ohman and Flatten could have been bad with distances and someone may have cleaned out the runes with a sharp tool to make it more legible, removing the patina and leaving crisp edges.

The cleaning might be believable if there was some missed patination and some of the edges were still weathered by nearly 600 years in the ground.

Problems with the Runes

In January of 1899, Swan J. Turnblad, a Swedish-American publisher in Minneapolis received a letter from J.P. Hedberg describing a stone found in a farm field that had some strange writing on it. Writing Hedberg described as appearing to be “old Greek letters.” Attached to the letter was a sketch of the stone’s two registers of text.

The sketch was done in pencil and was ultimately archived along with the letter by the Minnesota Historical Society, so is available for inspection and comparison. At least the digital version is.

the blue box highlights “blöd” vs. “blod;” the green box shows the erasure.

And this is where everything really gets interesting: the Hedburg sketch, though it is intended to be a one-for-one drawing by Hedburg of the original, had a few differences. These differences were errors made during the process of copying down the information from the stone to the paper. And they were precisely the sort of errors one might make if one was copying a sequence of letters from an alphabet one was quite familiar with.

If you’re going to sketch an image of a writing system you’re unfamiliar with, you check each pencil stroke against the original. If, however, you’re already familiar with the language and the script, you read a bit and write a bit. In doing so, it’s possible to make mistakes with words that have similar meanings but different spellings.

Take the English word “color” for instance. If you’re transcribing a paragraph, and you’re of British descent, you might be forgiven for writing “her eyes were the colour of the sky” instead of “her eyes were the color of the sky.”

In line 7 of the Hedberg sketch, Hedberg uses the runes for blöd; where as the KSR runes read blod. A native speaker of Swedish might not even notice the error at all since they’re essentially the same word. Several other equally minor mistakes were made in the Hedberg sketch. One of these was the pencil correction of one runic version of the word “dead” to another.

Problems with the Story

I already mentioned the competing dates of discovery above, but there’s also a competing discoverer. While both the affidavits from Ohman and Flatten agree that the stone was originally discovered by Ohman, Professor Newton H. Winchell, the state geologist for Minnesota (1873-1900), was on record with the Minnesota Historical Society (MHS) as saying it was Flaten who discovered the stone, didn’t initially see any writing on it, then let it “lay neglected for a long time.” Perhaps an honest mistake.

In his book, The Kensington Stone, Erik Wahlgren suggests that the stone might have been found twice! The first time by Nils Flaten in August of 1898, 500 feet from Flaten’s house in the swamp on Flatten’s own land. The second time, either the same or a similar stone was “found” 1200 feet from Flaten’s home on the small hill within the boundary of Ohman’s land. The first time uninscribed; the second time inscribed with the runes. This would seem to account for several of the discrepancies already mentioned.

Several key figures also denied having any knowledge of runes and runic writing. Specifically, Olof Ohman himself as well as J. P. Hedberg. Ohman initially denies recognition of the text as runes and wonders if it might be a “Indian almanac” due to the “strange writing.” Hedberg writes to Swedish-American publisher Swan Turnblad that “it appears to be old Greek letters…”

As it turns out, Ohman was very familiar with runes as was Kensington real estate businessman J. P. Hedberg.

Ohman owned a copy of an 1881 book by Carl Rosander, Den Kunskapsrike Skolmastaren (The Well-Informed Schoolmaster) which was self-described as “A Handbook of Useful Knowledge for all Social Classes.” This was a book of popular knowledge of the period, but it contained on page 61 a description of a variety of rune types along with a detailed discussion on rune stones, how they were made and where they were often found. Ohman’s ownership of the book is demonstrated by his signature inside the cover along with the date, March 2, 1891. Nearly 8 years before he discovered a stone with writing he supposedly didn’t recognize.

And Hedberg clearly understood runes enough to know they weren’t “old Greek letters” if he could mistakenly write one runic version of “blood” for another when he was supposedly transcribing line for line; shape for shape. The problem with the story then becomes: why do Ohman and Hedberg feel it necessary to pretend they don’t know anything about runes?

The Contemporary World

Many things were happening in the world contemporary to Olof Ohman and other Scandinavian immigrants to Minnesota.

The Dakota War of 1862. In 1862, following a harsh winter and a year of crop failure, members of the eastern Dakota Indians found themselves in desperation. They attempted to drive white settlers out of the Minnesota River valley and, over a span of several weeks, attacked and killed hundreds of settlers. Thousands of settlers fled the region.

The Dakota War of 1862, sometimes referred to as the Sioux Uprising, was brief but brutal, lasting from August 18 through September 26 in 1862. By its end, over 350 settlers and 100 U.S. military were killed. The total number of Dakota casualties is unknown, but some estimate as many as 150 Dakota soldiers not including the 38 who were executed in December 1862 for their involvement.

You might ask, “what does this have to do with the KSR?” But this all occurred just a few decades prior to Ohman immigrating to Douglas County, just a few counties away from the conflict, and finding the KSR. Entitlement to fertile land must still have been a topic of thought. Also, there’s the curious date of 1362 for an Indian attack on the 8 Goths and 22 Norsemen that left 10 of their party dead included on the KSR inscription that could be seen as a nod to 1862 assuming it was hoaxed.

Ignatius Donnelly and Atlantis? Interestingly, in 1857, Ignatious Donnelly arrived in Minnesota where he served as the Lieutenant Governor from 1863 to 1869. After that, he continued to be a figure in politics with he Populist Party. In 1882, he gained global fame with his book, Atlantis: the Antideluvian World. In this book, at the end of chapter IV, Donnelly cites Alexander von Humbolt, “We have fixed the special attention of our readers upon this Votan, or Wodan, an American who appears of the same family with the Wods or Odins of the Goths and of the people of Celtic origin… “ and continues on to say, “Odin and Buddha are probably the same person” (Donnelly 1882, p. 135).

Rasmus B. Anderson (1874). America Not Discovered by Columbus was published by Anderson, a professor at the University of Wisconsin, and describes claims that early Norsemen were the discoverers of North America.

Rasmus Anderson also mentions Humbolt in his Snorre’s Edda (Chicago 1880): “According to Humbolt a race in Guatemala, Mexico, claim to be descended from Votan… This suggests the question whether Odin’s name may not have been brought to America by the Norse discoverers in the 10th and 11th centuries, and adopted by some of the native races.”

The influence of Humbolt. Alexander Humbolt’s Vues des Cordilleres, et monumens des peuples indigenes de l’Amerique, was originally published in 1810 and was in French. But Anderson and Donnelly were both contemporary to the year the KSR was discovered.

Gustav Storm (1888). Storm’s Studier over Vinlandsreiserne, Vinlands Geografi og Etnografi (Studies into the Vinland Travelers, Vinland’s Geography and Ethnography) includes a disagreement with Anderson (1874) in chapter 8. Sections of this book were published in a series that ran in a Swedish language newspaper in 1889 in the United States and available in Minnesota.

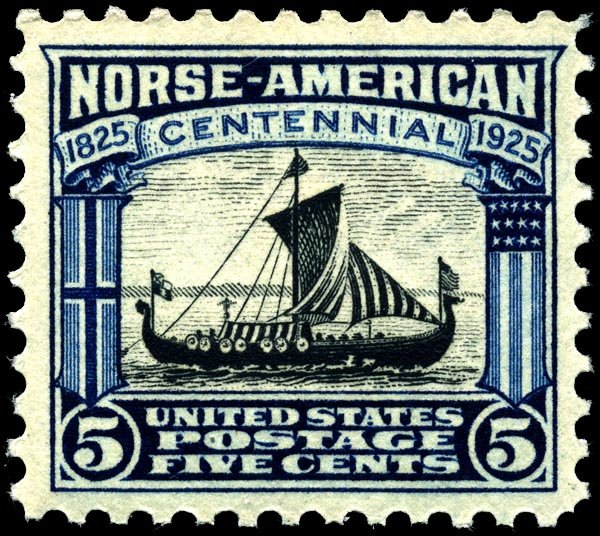

The Gokstad and the Chicago World’s Fair. In 1893, a replica of the Gokstad sailed to the United States for the World’s Fair in Chicago which was big news. It even earned its own postage stamp and is, today, on display at the Good Templar Park in Geneva, Illinois.

A 19th Century Hoax that Endures into the 21st

Interestingly, the word “opdagelse” (discovery), appears in varied forms at least 28 times in Storm’s text and the form Opdagelsfard appears in line 2 of the KSR inscription. Opdagelse is a modern Danish-Norwegian word, not a medieval one of the 14th century as the KSR claims itself to be, and is mixed on the KSR with Swedish words. As one might expect from a 19th century creation in a part of Minnesota where there is a mix of Swedish and Norwegian speaking people.

As indicated above, the style of text to include spelling choices, grammar, and other linguistic attributes really does preclude this from being a medieval inscription. This just isn’t how things were written and said in the 14th century. It is, however, consistent with how someone in a Swedish-Norwegian community of Minnesota might have imagined it.

The physical attributes of the inscription itself is fresh. Not patinated or worn. Sure, proponents will claim it was “cleaned” with a nail, file, etc. But this is just too consistent. Moreover, such damage of archaeological context is good enough reason to discard or discount the stone as genuine without other, better evidence. Particularly when the text itself presents as modern.

This and much circumstantial evidence points to a 19th century hoax. A bit of fraud that probably was never intended to become an international sensation that seems to endure even today. What was probably just a fun project among friends (Ohman and Flaten) perhaps spiraled out of control as the romance and intrigue associated with Vikings in America was easily accepted. The newspaper and magazine articles, the books, the public talks all quickly left Ohman and Flaten behind.

Even if they created it, my opinion is that they’re as much a victim of the hoax as anyone.

Sources and Further Reading

Anderson, Rasmus B., ed., (1883). America Not Discovered by Columbus. Chicago, S. C. Griggs.

Anderson, Rasmus B (1920). Another View of the Kensington Rune Stone. Wisconsin Magazine of History. 3, 1-9.

Flom, George T (1910). The Kensington Rune-Stone: A modern inscription from Douglas County, Minnesota. Publications of the Illinois State Historical Library. Illinois State Historical Society, 15, 3-44.

Hall, Robert A., Jr. (1982). The Kensington Rune-stone is Genuine: Linguistic, practical, methodological considerations. Columbia, SC: Hornbeam Press.

Kehoe, Alice Beck (2005). The Kensington Runestone: Approaching a Research Question Holistically. Long Grove, IL. Waveland Press.

Kehoe, Alice Beck (2008). Controversies in Archaeology. New York. Taylor & Francis Group.

Nielsen, Richard, and Scott F. Wolter (2006). The Kensington Runestone: Compelling New Evidence. St. Paul, MN. Lake Superior Agate Publishing.

Wallace, Birgitta (2006). The Kensington Runestone: Approaching a Research Question Holistically by Alice B. Kehoe, a Review. Canadian Journal of Archaeology / Journal Canadien d’Archéologie, 30(1), 143-149.

Wahlgren, Erik (1958). The Kensington Stone: a Mystery Solved. Madison, WI. The University of Wisconsin Press.

Williams, Henrik (2012). The Kensington Runestone: Fact and Fiction. The Swedish-American Historical Quarterly, 63(1), 3-22.

Unfortunately for millions fee-fees over facts are their ‘reality’.

Very interesting post! I’ve as a native Swedish speaker had a lot of fun reading the “Den Kunskapsrike Skolmastaren” which you so kindly linked.