This is a slightly edited version of an article I wrote on this blog back in 2010. When does vandalism become an archaeological feature? When it’s done in antiquity, of course.

In the featured image of this article above is a photo of a particular kind of vandalism commonly referred to as “pilgrim gouges.” I’ve noticed these peculiar scoops of stone in various photos of columns, ashlar blocks, monuments and so on, but never really stopped to think about what they were.

In hindsight, all the examples I can think of or locate on the net or in books, are within reach of people. Still, my first guesses included eroded palimpsests and some sort of vandalism in antiquity.

Palimpsests in this sort of context are places where one set of inscriptions or a bas relief is removed or plastered over to create a new set of inscriptions or a new bas relief. This wasn’t an uncommon practice in ancient Egypt -sometimes one ruler wanted to substitute his own name or beatitudes or perhaps curses of an enemy.

Sometimes a bit of vandalism occurred in antiquity when a subsequent ruler was unhappy with a predecessor or if a new culture just simply had no regard for a much older one. There are monuments with graffiti etched by Greeks and Romans in Egypt and there are monuments around Europe and the Middle East that have bullet holes that could only have been deliberate vandalism.

But the curious little scoops and gouges in the stones of Egyptian monuments and reliefs at places like Karnak are something different. One thing they seem to have in common is that they are typically vertical and that they are deeper in the center, as if scooped out.

It turns out that Pilgrims and believers in magic scraped the stone to remove a fine dust, which they collected and mixed in a drink. By scraping out a portion of the temple or monument, the pilgrim hoped to obtain some of the power through sympathetic magic. This practice occurred from about the time of the New Kingdom to around the 5th century CE (Franfurter 2000).

[Flickr: CC BY 2.0]

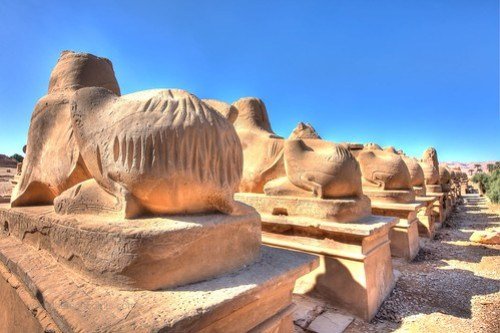

What’s interesting about the practice is the frequency and distribution of the “gouging.” Deeper gouges indicate more attention spent at a particular gouge over time (a single gouge probably wasn’t produced by a single pilgrim at a single visit), as do more gouges at a particular spot. The sphinx above, for instance, has more, deeper gouges than it’s neighbor tot he right. Both of these have more than other neighboring sphinxes, and so on, suggesting that the first two, in particular the first, has more perceived power than the others.

Or perhaps more accessibility. Gouging by pilgrims was not random and the distribution tended to be concentrated in certain areas such as “outer corners of buildings, hypostyle pillars, and certain hieroglyphs and divine faces on outside walls (Frankfurter 2000). So while there was the concern of the object’s power, there was also an obvious concern of accessibility. The sphinx above may have been easier to scrape without being observed by those that might interfere (caretakers of the temple) or it might have been perceived as the more powerful of the sphinxes (i.e. its position in the line along the avenue).

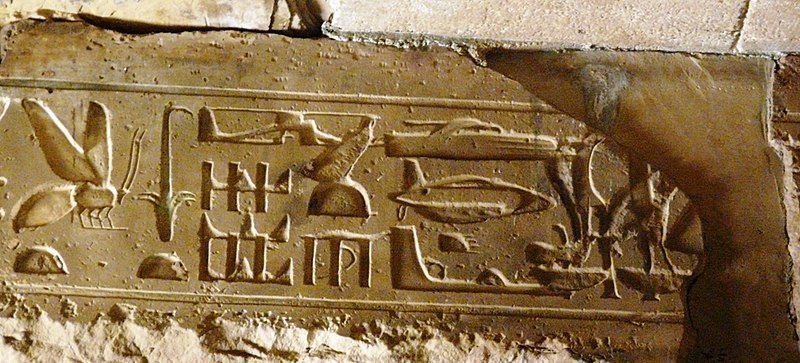

It wasn’t always an image or a temple, which are obvious places to perceive power, but also writing. The gouges on the Ramesses II‘s treaty with the Hittites above may be written on a temple wall, but the gouges themselves are grouped together in ways that suggest it wasn’t the wall or the temple that had the power, but the words of the inscriptions that resided there.

Pilgrim gouges are a fascinating topic. Anyone who’s visited Karnak or stared at photos of Karnak for hours as I have will probably have noticed them. Originally, it was a reader of my blog back in 2010 that commented or emailed me a question about them that made me pay attention. Since I wrote the original blog article back in 2010, there’s been some study of the practice.

In the International Journal of Heritage Studies, Troels Kristensen wrote the article, “Pilgrimage, devotional practices and the consumption of sacred places in ancient Egypt and contemporary Syria.” There, Kristensen concludes, “The pilgrim’s gouges add to our understanding of the relationship between the consumption of sacred spaces and pilgrimage in a cross-cultural perspective,” and help us to “understand the multifaceted relationships that exist between materiality and the consumption of sacred places.”

In other words, studying these archaeological remnants, that are essentially vandalism, give us some insight into how people of one period in antiquity used and consumed the sacred spaces of another, earlier period.

There really is a lot to chew on in that small, intellectual snack.

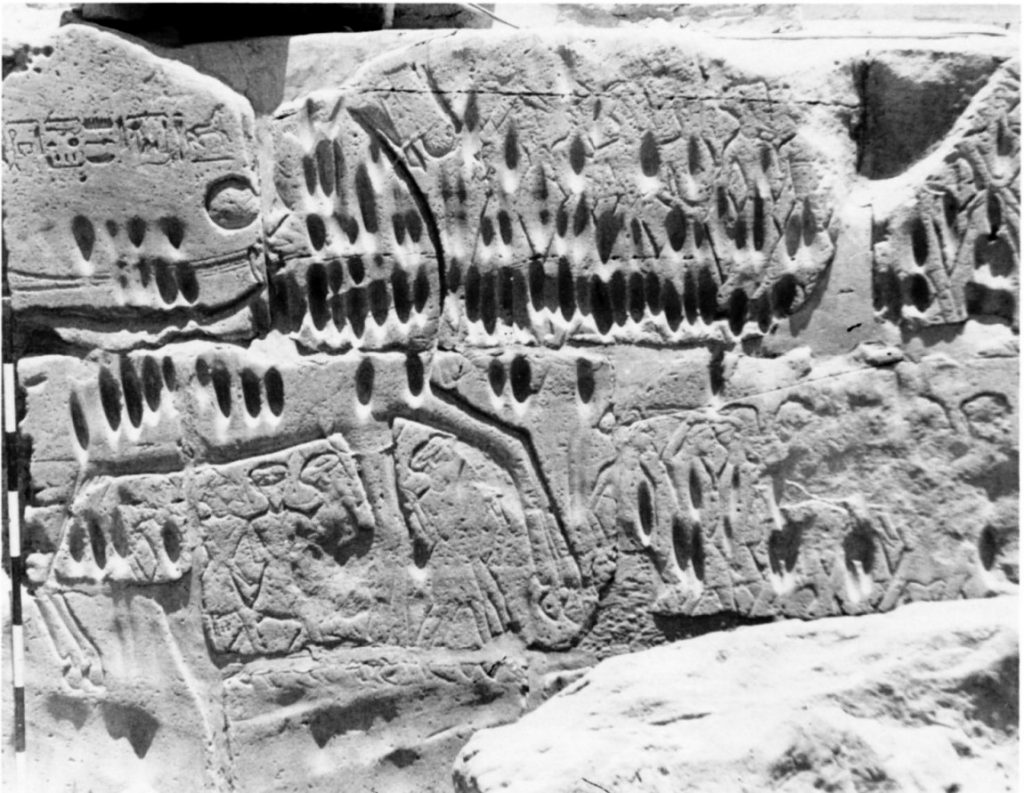

To give you an idea of how ubiquitous these little pilgrim gouges really are, here are some photos from Redford (1986). This was one of the first things I read where I noticed the gouges and was perplexed that Redford never mentions them except to essentially say that it was frustrating not being able to read the information in cartouches.

Ramesses II binding the Shasu prisoners. From Redford 1986.

Close up of the cartouches in the Ramesses II bas relief. Note the obliteration of writing by pilgrim gouges. Photo from Redford 1986.

Marching off the Shasu prisoners. The gouges have a distinct pattern. From Redford 1986.

Sources and Further Reading

Frankfurter, David (2000). Religion in Roman Egypt: Assimilation and Resistance. Princeton University Press, pp. 51-52.

Kristensen, T.M. (2014). Pilgrimage, devotional practices and the consumption of sacred places in ancient Egypt and contemporary Syria. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 21(4), 354-368.

Redford, Donald B. (1986). The Ashkelon Relief at Karnak and the Israel Stela. Israel Exploration Journal, 36(3/4), 188-200.

Good article Carl: as a non-specialist, while I’ve viewed plenty of photographs dealing with Ancient Egypt, this was new to me, or at least I never noticed those marks before. I might have suspected it was some type of damage, but would have never guessed the actual reason behind it…

A lot of fake relics and artifacts were circulating around Europe centuries ago. I wonder how many unsuspecting buyers in circa-1200 England purchased bags of dust that was supposed to have been scrapings from a holy site in Israel but came from the next town over?