In 2015 I wrote a quick article, Sumerians in Bolivia? Probably Not, in which I very briefly described and criticized the Fuente Magna Bowl–a so-called “out of place artifact (oopart)” that seems to make the social media news feeds every month or so.

In that article, I said, “such an artifact would be very significant and among the most note-worthy finds of the human past if: 1) it could be dated to a pre-Columbian period; and 2) the writing was genuinely Sumerian.” And I also said, “there is no provenience. Non. Nada. Zilch.”

And I stand by everything I said then.

But, because this silly thing is actually pretty interesting and a good example of how the so-called “oopart” phenomenon can get in someone’s head, I felt it was worth taking a closer look at. And because Keith Fitzpatrick-Matthews criticizes my second statement above about there being no provenience on his Bad Archaeology blog (an excellent blog, by an excellent writer), I want to take a moment to clarify that point first.

I don’t know Keith personally, but I did notice that we’re using the term Provenience differently and that’s probably more my fault than his. Here’s what he wrote regarding my statement:

The bowl has also been a problem for debunkers. Most seem happy to dismiss it as a hoax having no provenance. This is a little unfair. Whatever we might think of the work of Bernardo Biados and Freddy Arce, they did actually travel to the alleged site of its discovery and interviewed the person who claimed to have found it. This is very different from asserting that “there is no provenience. None. Nada. Zilch. We have anecdotes of it being “discovered””. As we’ve seen, this isn’t quite the case. The provenance may not be secure, but there is at least a likely location.

I’m not going to begrudge Keith for the critique. It was my hope that what I meant by provenience would have been clear in the context of my writing. That he didn’t get it as a professional in the same field says more about me as a writer than he as a reader. I’d also highly recommend visiting his blog and reading his take on the Fuente Magna Bowl. He clearly spent some time tracking down anything and everything that was written about it and found who allegedly “discovered” the bowl.

Provenance vs. Provenience

What Keith found was the bowl’s pedigree. It’s provenance. The chain of custody to the earliest known person.

What he didn’t find is the bowl’s provenience. And, as a practicing, dirt-digging archaeologist, this word, similarly spelled, has similar but different meaning than the word provenance. It isn’t just a matter of swapping or adding letters as with “realize” vs. “realise” or “color” vs. “colour” when translating between American and British English. Provenance is a chain of custody, as with a work of art. Provenience, however, is the x-y coordinates of a find within it’s unit. The context it has with all the other artifacts and features from which it was dug. And that’s the vital thing that’s missing from the Fuente Magna Bowl.

Without a solid provenience, and even if the artifact were genuine, the best that could be said is, “isn’t it curious how a Sumerian stone bowl ended up in Bolivia?” We could only assume that a traveler picked it up in a market, or looted it from a genuine site in the Near East for resale which may or may not have occurred. Then it was lost to be found again by some lucky person. If, however, it had been found in a genuine site, then the context would be key to understanding it. Was it found in a trash midden? A burned house? A camp or hunting station? What were the artifacts associated with it? Were there 1940s or 1950s travel brochures or post cards found with it? Or was it truly found from a layer that dated to Sumerian times?

The likely answer, however, is that it was forged. A complete and utter hoax. And the rest of this article tells why.

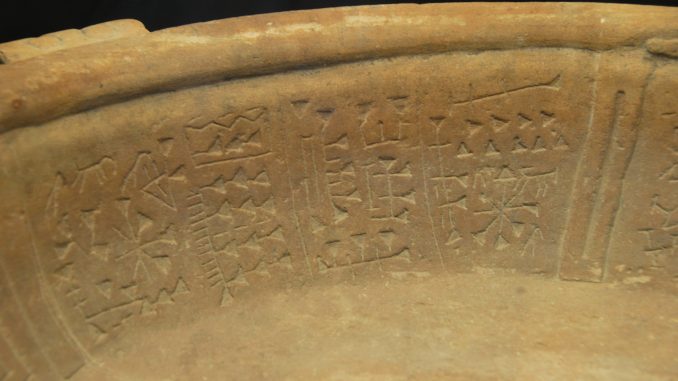

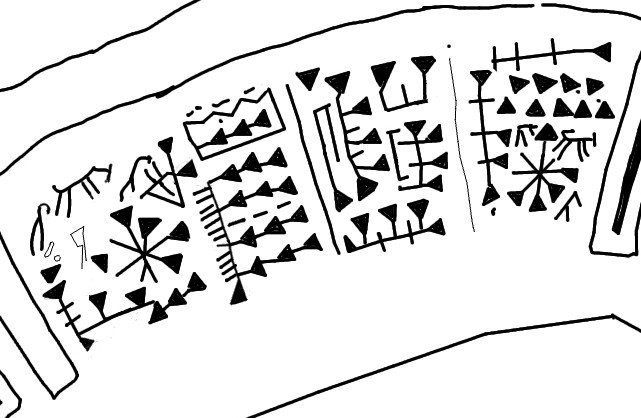

Three sets of writing

There are at least three sets of alleged “writing” on the bowl. All three are somewhat different but similar in some ways as well. There’s what has been called both “Phoenician and Proto-Sumerian on the left side of the bowl, represented mainly by linear glyphs that have a few cuneiform-like wedges scattered about. On the right side of the bowl is a clear attempt at cuneiform, with wedges that generally point the wrong direction and the inclusion of a few glyphs that look like they could belong to the left side. Then there’s the center panel, bisected by an anthropomorph in the middle of what appears to be a linear style similar to the left side, thought with less complexity.

Translations

As Keith points out, there are a couple of people who claim to have figured out the writing. One is the late anthropologist Hugh Fox, who was a professor at Michigan State University. He claimed that the writing was Phoenician, though he doesn’t seem to have provided a translation anywhere. The source of his identification he said was Sign, Symbol and Script,” by Hans Jensen (1969).

Clyde Winters, a former professor of education at Governer’s State University in Chicago, claims that the writing is Sumerian. The right side of the bowl he says is Sumerian cuneiform and the left side is “Proto-Sumerian.” The problem is the signs don’t match the transliterations he claims. And Winters’ translation is the most prominent one to come across when you search the internet for “Fuente Magna translation.”

Also, “proto-Sumerian” really isn’t a thing. Sumerian is the language that was expressed by cuneiform script. Think of a book written in English using the Roman alphabet. Another book might be written in Spanish using the same Roman alphabet. You’ll recognize the letters and many of the pronunciations, but unless you speak the language, much of the text is meaningless. This is the same with cuneiform in a way. Languages that might use cuneiform script are Sumerian, Akkadian, Assyrian, Hittite, and some others. So, instead of “proto-Sumerian” script, Winters probably meant proto-cuneiform. For which there is a syllabary of known signs. In any case, the symbols in cuneiform don’t generally look all that different from language to language, but the meanings of the symbols do change.

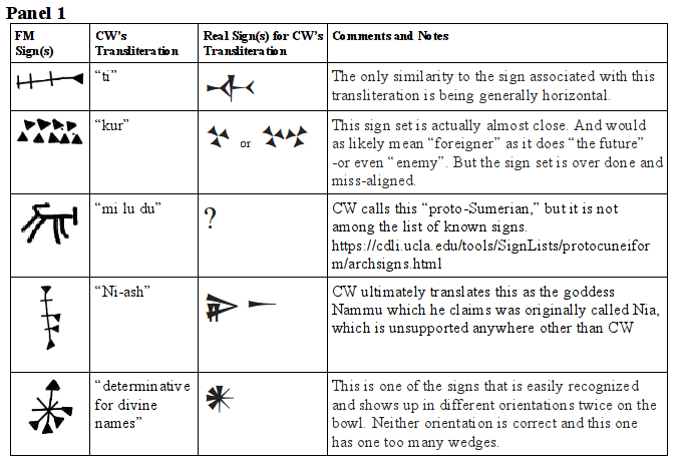

To illustrate the problems in detail, let’s look at the symbols on the bowl as he pretends to translate them on his own website. I’ve made some tables that can serve as visual aids.

In the table above, you can see the signs that Winters has identified with his pretended transliteration in the next column. In the 3rd column are the actual signs for the transliterations Winters claims. But honestly, only two symbols came close to being real. They were, perhaps, the two easiest to remember for someone looking at a book of cuneiform texts. The two are DINGIR / AN and ASH. The rest were nonsense. KUR was the next closest, but it, too, had the appearance of being very sloppily done if we’re to accept it as actually being KUR. In this Panel there is also the introduction of one “proto-Sumerian” sign (to use Winters’ description). The problem is it doesn’t show up on the list of known proto-cuneiform signs. Check for yourself. Nor does it show up in any other sign or syllabary list that I looked at. If someone finds it, I’d love to know where.

The problem with DINGIR / AN in this panel is two-fold: 1) it’s upside down; 2) it has one too many wedges. There should be 4 wedges but there are 5. KUR has 3 too many wedges and they are not correctly aligned. TI is horizontal as it should be (in this panel), but looks nothing like it should. NI-ASH looks nothing at all like it should. Moreover, Winters claims this is a translation of the goddess Namma which was originally called Nia. This seems only supported by Winters himself and no where independently, though I’d love to hear from someone that has different information. In any case, the sign for NI-ASH is much different than which Winters claims.

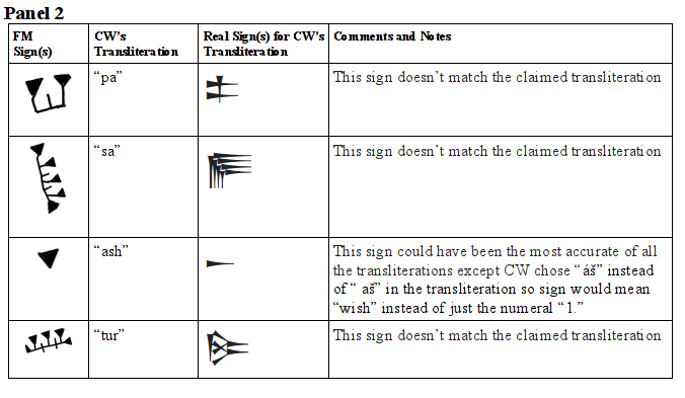

As you can see in this table, the only sign that comes close to matching what Winters claims is ASH. The rest of the transliterations appear completely made up.

In this panel, three signs come close to matching the signs Winters claims they should be. Ash and DINGIR / AN are extremely close. DINGIR / AN isn’t upside down this time, but it is flipped 180 degrees horizontally. But it does only have 4 wedges this time. Eš is pretty close, but the wedges are facing the wrong way, but this is consistent throughout the bowl’s supposed cuneiform script. Winters also spells it “esh” which can be confusing. But the configuration is essentially “three ASH” or the numeral 3. This time TI is not horizontal but vertical and it still looks nothing like TI. And this time there are 3 “proto-Sumerian” signs that, again, match no sign in the complete list of proto-cuneiform syllabary.

Here are the three panels that Winters pretended to translate, with his psuedo-transliterations/translations below.

The pseduo-transliteration*:

Ti Kur kur kur kur (determinative for divine names) Nia (lit. ni-ash)

Pa en ash sa tur

Zi esh, Esh esh, esh esh.

Pap pa ge Lu ta mi du lu ta

Bar nu ash

Ash ti en

The psuedo-interpretation of his pseudo-transliteration*:

“Approach in the future (one) endowed with great protection the great Nia”.

[The Divine One Nia(sh) to] Establish Purity, Establish Gladness, Establish Character”

“[Use this talisman (the Fuente bowl)] To sprout [oh] diviner the unique advise [at] the temple”.

“The righteous shrine, anoint (this) shrine, anoint (this) shrine; The leader takes an oath [to] Establish purity, a favorable oracle (and to) Establish character. [Oh leader of the cult] Open up a unique light [for all], [who] wish for a noble life”.

* Both were taken from Clyde Winters’ Reocities (formerly Geocities) website here, last updated 10/29/2009.

Summary

Looking at this bowl from a perspective that says, “okay, what if it’s real? What can we learn from the text?” shows that it just isn’t real at all.

The attempt at recreating cuneiform is sloppy: wedges are pointing the wrong way, the one that looks like it might be right is upside down and backward (DINGIR / AN; nearly all of the signs are not in any known sign-list or syllabary; and non-cuneiform signs are mixed in. The other “writing” on the bowl has a similar look and feel as scripts like Phoenician and Prot0-Sinaitic script (also called Proto-Canaanite)–but not quite. Also, cuneiform is generally very rigidly arranged in nice, tidy rows and columns, whereas the “script” on the bowl is haphazard and Winters insists it’s to be read from right to left! Cuneiform was generally read top to bottom, left to right, flipping the tablet on the short edge.

Overall, the “writing” on the bowl has the look and feel of being created by someone who actually saw some cuneiform and maybe some Proto-Sinaitic. But when they went to create the bowl, they didn’t have these sources in front of them. Maybe the carver visited a museum. Or maybe watched a newsreel. Or read a story in Life Magazine–one such story ran in the March 15, 1948 issue with the title “Babylonian Mail: A Yale professor reads documents written more than 4,000 years ago.” There were some photos of the tablets.

The writing on the bowl is nonsensical. And the translation of Clyde Winters even more so.

The bowl itself is without archaeological provenience–no context or actual find-site.

It was likely created shortly before it was allegedly found. And the reason there’s no archaeological provenience is because, well it wasn’t an archaeological find.

Further Reading

Halloran, John A. Sumerian Lexicon Version 3.0 and PDF here.

Jensen, Hans (1969). Sign, Symbol and Script. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, NY.

http://www.boliviaentusmanos.com/turismo/destinos/museo-de-metales-preciosos.html

look at the smile on that bowl in the photo, is that a sincere bowl? Hell no, that bowl is clearly up to no good, looks like Kermit the Frog caught cheating on Miss Piggy.

BTW, I took a quick search and didn’t find any other bowls with cuneiform writing on them – what luck that these folks found the one & only!

The most recent radiocarbon dating of artifacts suggests Tiahuanaco was founded around 100 AD, there have been no ceramics/pottery/stonework dating to earlier periods of occupation. The one of a kind bowl, to my knowledge, has never been radiocarbon dated, and age has been erroneously attributed only to the forged symbols (triangles & lines) which are unlike any artifact of Sumerian, Phoenician or early Fertile Crescent pottery, proto- or otherwise. There have been no chemical tests of the materials used to create the bowl.

It’s unlikely an artifact would have survived a Trans-Atlantic or Trans-Pacific trek. Sumerians only traveled along coastal routes to parts of North Africa and India never venturing into truly open seas.

If Sumerians were in South America they certainly didn’t share the wheel, or any other advancements in industry, with the inhabitants, nor taught them how to write in proper Cuneiform. The wheel would have been necessary in a large tin mining operation. The bowl was “found” by a construction worker in the 1950s who worked for the Manjon family.

This is the least impressive slandering of diligent Archaeology I have yet seen. Creating a pathetic slander site to mock legitimate field work is pathetic. Your handiwork is openly ridiculed by professors and real academics. it is widely known that the Cuneiform Writing in the bowl is not Sumerian. it clearly displays symbols from Proto Elamite and other types of Cuneiform. Obviously you never bothered to cross compare your results with Tamazigh language samples from Libya. I have never hear anyone who is a legitimate archaeologist try to slander or debase genuine findings in such a manner. Obviously you are the hoaxster, here, on this pathetic joke of a trash page you seem to be so proud of. I condemn you sir, to obscurity and lack of attention. Your trivial interpretations have been overridden by legitimate archaeologists whom are employed by genuine Research Institutions. You shame yourself sir, and the rest of us…

“This is the least impressive slandering of diligent Archaeology I have yet seen.”

LOL. This leaves us all wondering what slanderings of diligent archaeology actually impressed you! It probably doesn’t matter, because you’re clearly talking about something else other than the article above. I was critiquing Clyde Winters’ claim (and others) that the Fuente Magna bowl actually has cuneiform on it and that it’s an artifact of Sumerian origin. Not “diligent archaeology.”

“Creating a pathetic slander site to mock legitimate field work is pathetic.”

Well, it’s a good thing I’ve not done that here then! Slander is the act of making false *spoken* statements damaging a person’s reputation. I think you meant to claim I was libelous. Libel is the act of making *written* statements that are false and damage a person’s reputation. If this were a slander site, it would be a podcast.

However, I’ve also not engaged in libel! But let’s take a look at the reasons you might think so:

“Your handiwork is openly ridiculed by professors and real academics.”

It is? Could you perhaps link to my colleagues’ comments where they are openly ridiculing my work? Be it handy or not?

“it is widely known that the Cuneiform Writing in the bowl is not Sumerian.”

Yes! Thanks to me, given that my article on the “Fuente Magna bowl” is the number two link on a google search for that term!

“it clearly displays symbols from Proto Elamite and other types of Cuneiform”

Nope. Not even. In fact, I demonstrated that in the article above.

“Obviously you never bothered to cross compare your results with Tamazigh language samples from Libya.”

“Now I’m confused. Are you saying that the Fuente Maga bowl is in proto-Elamite writing (which would be from a region that is roughly modern-day Iran) or Tamazight writing (which would be in Libya–about 4,000 miles away)?

Incidentally, I think the word you were looking for for the Berber culture whose writing you like is either Amazigh or Tamazight depending if you’re referring to the people or the language respectively.

“I have never hear anyone who is a legitimate archaeologist try to slander or debase genuine findings in such a manner.”

If you think these are “legitimate findings” you clearly don’t get out much.

“Obviously you are the hoaxster, here, on this pathetic joke of a trash page you seem to be so proud of. I condemn you sir, to obscurity and lack of attention.”

Oh, noes!

(I think I’ll survive)

“Your trivial interpretations have been overridden by legitimate archaeologists whom are employed by genuine Research Institutions.”

Since your object was “legitimate archaeologists,” “whom are employed by genuine research institutions” is a new phrase with its own subject, so you would use “who” rather than “whom.” It can be confusing, so easily forgiven. (Rule of thumb: if you can replace “whom” with “him” or “them” without sounding like Tarzan, it’s probably right).

But joking and grammar lessons aside: can you cite the “legitimate archaeologists” of whom you refer?

“You shame yourself sir, and the rest of us…”

You might be half right…

Seriously though. I laid out the evidence by showing the work. I will admit there are some similarities with Tamazight writing. And you are correct, I didn’t compare with their writing. Nor did I compare with the proto-scripts and obscure writings of several other languages. There are some similarities to Rongorongo and Vin?a symbology and probably a dozen others that I also didn’t compare with.

The reason is they weren’t relevant since no one was making a claim that they were.

If you are so insistent that I’m wrong, and would like to see me admit it, all you have to do is show the translation. Winters didn’t do it. Hugh Fox didn’t do it. Maybe you, my anonymous friend, could be the one.