There have been a few articles in online media recently that highlight the relationship possible for metal detector hobbyists and archaeologists where the recreational metal detectorists assist in locating sites that are ultimately excavated properly and might never have even been discovered had it not been for the metal detectorists doing their thing.

This, I think is all well and good. It shows the viability of the metal detector as a tool to be used in archaeology, something my shop makes occasional use of (they’re wielded by professional archaeologists, not local hobbyists). Some of my colleagues even have good relationships with the metal dectectorists in their local communities and Martin Rundkvist writes positive things about what they do in Sweden. I even follow the Facebook page of Scott Clark (Kentucky Unearthed), who I find to be generally responsible and interesting.

I recently chanced upon a forum post at Treasure Net titled, “How to Get Away With Metal Detecting Protected Battlefields!,” and thought it might be something I should read since the Forest I work on has a protected, albeit small, battlefield. I thought I should know what it is they’re up to.

I have to say I was somewhat surprised at the post. It wasn’t the list of tips and tricks on how to get one over on the government. In fact, it was a set of links and reposts of a the well-written documentation on the projects conducted by the National Park Service over the last few decades at the battlefield of Little Big Horn. This series of projects, which began to use volunteer metal detectorists in 1992, was ultimately able to follow troop movements across the battlefield by comparing artifact locations to unique signatures of firing pin marks.

For a wonderful narrative on how the results have informed our new understanding of that battle, have a listen to Joe Schuldenrein’s podast where he interviews Douglass Scott.

Another project the Treasure Net poster highlighted waas a re-post of the NPS article on the Battlefield Archaeology at Kings Mountain National Military Park in South Carolina. The conclusion included:

This project clearly shows the level of information collection possible using a group of dedicated volunteer metal detector hobbyists. Without the metal detector hobbyists volunteering their time, none of the new information about the Kings Mountain battle would be available to the public. The relationship has been one of mutual benefit, as volunteers are able to work in places to which they would not otherwise have access and they can handle and photograph the artifacts found. This gives them “bragging rights” and additional information about material culture.

The most useful data from these projects came from the ability to pin-flag the hits from the metal detectors, associate them with individual artifacts, then view their contexts in relation to each other and the battlefield landscapes.

There’s no denying that the chance of locating historic objects long forgotten under the ground has an alluring appeal. Certainly for some there is the chance to make a buck, and metal detectorists I’ve watched on popular television shows in the past immediately place a dollar value on objects they find. Treasure hunting magazines published for metal detectorists nearly always highlight the “treasure” and monetary aspect of finds.

But the romance and intrigue of finding an object like a belt buckle, ring, or coin that was last handled 150 or more years ago is probably a huge part of the reason people gravitate toward the hobby. Hell, it’s one of the reasons I’m an archaeologist. The stories these objects can potentially tell are fascinating. The objects speak to us. It’s a hobby that puts you in touch with the past, historic places and times, the tales and legends remembered by modern people, and the outdoors all at once.

But it all comes at a price.

Commenters of the Treasure Net post showed the ugly side of the metal detector hobby that archaeologists fear most, which is the casual disregard for that which is the most valuable in any historic site. Context. Here are two standout comments:

“However, I hate to burst yours, or anyone else’s bubble, but ……. volunteering to help archies isn’t as exciting as that would make it out to be. You have to flag the signal. Archie’s come over and go through meticulous dig process (with tweezers, brush, etc…). And they write a volume of notes on each target (the depth, the angle, the GPS, the association with any other pebble or piece of ash in the hole, etc…). It’s not like the md’r is allowed to dig any of the signals (in our normal fashion we are accustomed to). ”

“So, in essence, the archies can’t man/finance the project so they use volunteers from the very group who they are trying to get restricted at every turn. And, those being restricted are actually helping. Sorry, I see absolutely zero mutual gain at all. Quite the opposite. But that’s just me.”

There were definitely a few positive comments. Roughly half. Folks that said they would be thrilled to work closely with archaeologists and have their finds used in research or displayed in a museum. But the roughly half of the comments that were negative are worrisome. They were vehemently anti-archaeologist, anti-government, and unwilling to give in to any sort of cultural heritage motive that supersedes their own ideas of what it means to uncover historical objects.

I think I get their frustration. They’re constantly restricted. Constantly told what they can or cannot do. Constantly criticized and referred to as “looters” even when they detect on private lands (in the U.S.–laws are much different in most other nations). And so on.

The arguments from their side are probably along the lines of, “if I didn’t dig it up, it would be lost forever,” and, “why do Archies have any more right to history than me?”

There’s some merit to these arguments (and probably with other arguments the anti-archaeology metal detectorists would make), but they don’t erase the fact that once the object is removed from the ground, its gone. Along with its context. And how that artifact was positioned, what its position was, and how it related to the landscape and other artifacts around it, which can all be the most valuable information about a site.

Metal detectorists aren’t generally looking for sites. They’re looking for individual objects. Archaeologists are looking at the bigger picture and want more data than “I found these here bullets.” There are, however, the exceptions, which is why I subscribe to Scott Clark’s FB page. On 3/20/2017, he posted a 342 word article on his page about a school lunch token he found at 13 inches deep. That impresses me and Clark is clearly in to what he’s doing for the right reasons. I’m not sure I agree with his methodology 100%, but I definitely find it hard to be critical.

There remains a dilemma for archaeologists when it comes to metal detecting in the hands of hobbyists. One the one hand, it has the potential to broaden our ability to find sites, document them, and do research. On the other hand, there is the potential to lose forever sites that associated with a metal artifact that is now plucked from the ground.

That belt buckle and set of cartridges were metallic beacons, pointing the way to the non-ferrous objects and features of a bigger site: a hearth, a bit of fabric from a uniform left behind from a hasty retreat, and pile of discarded bones from a cooked meal. Those bits are still there. Perhaps the hobbyist with his metal detector kept notes, and recorded the GPS coordinates within centimeter accuracy (or even a meter!)… perhaps that data will be forwarded on to an archaeologist or the SHPO. Somehow I doubt, however, the average metal detectorist would, or even knows what a SHPO is.

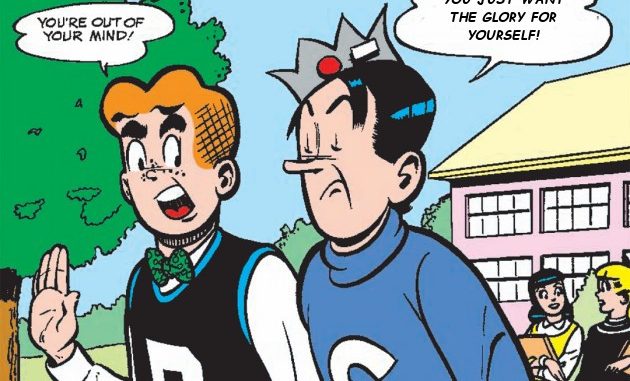

Hopefully the day will come when a common ground is found between the Archies and the Jugheads.

About the Feature Image

The metal detectorists seem to consistently refer to archaeologists as “the Archies.” So I suppose it’s fair to call them the Jugheads. But don’t assume that’s an insult. It isn’t. Jughead was always a bit laid back, even lazy (the detectorists are always wanting the shortcut to the artifact, avoiding the documentation we archaeologists like). But he was a smart dude. So are the detectorists. They might not be degreed, professional archaeologists, but many, if not most have at good understandings of their local histories and are very competent in predicting where to find artifacts. Like Jughead, it’s easy to under-estimate them.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.