Two different papers describe two different human footprints of the past from two very different locations in space and time across the Americas.

Footprints, in general, are a fairly rare thing to find in archaeological contexts since so many variables have to come together for the prints to form and then preserve in a way that they aren’t destroyed days, months, years, or millennia after they’re laid down.

Because of this and the very clear human connection, footprints are one of the coolest discoveries an archaeologist can make. Here are two published in recent days.

Chile, 15,600 BP

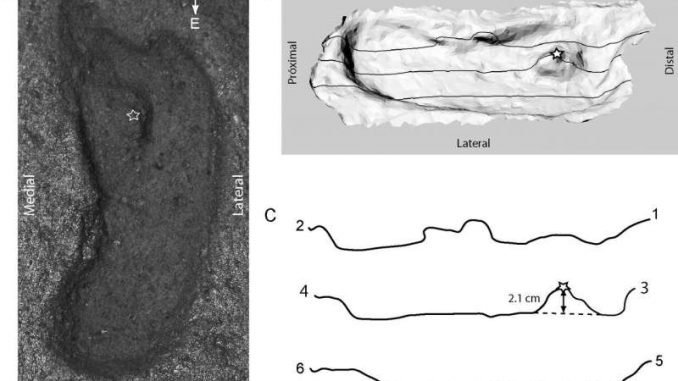

In a recent paper published by PLoS ONE, archaeologists describe a footprint excavated at a site in Chile, South America called Pilauco. The fossil footprint is in a late Pleistocene sediment dating to about 15,600 calibrated years BP and appears to be the oldest known human footprint in the Americas.

To add a little context, the late Pleistocene site of Monte Verde is also in Chile and dates to about 14,600 calibrated years BP, approximately 1,000 years after the newly discovered footprint’s potential date. More recent work at Monte Verde, however, puts its age at potentially 18,500 cal BP.

Paleontologist Karen Moreno and archaeologists and geologists from several institutions in Chile, including the Austral University, believe that the footprint is the result of a bare-footed adult human who stepped in “saturated substrate.” Essentially, mud.

Also found were lithic artifacts in the same sedimentary levels (unifacial objects, flakes, and debitage) along with late Pleistocene bones of mammals, invertebrates, seeds, wood fragments, and other remnants of Pleistocene flora.

The date was obtained by radiocarbon analysis of wood and vegetal remains. The team also conducted a series of experimental tests in order to evaluate different scenarios in which the footprint could be formed.

No doubt this find will meet with some measure of skepticism since the footprint is poorly defined and the age is at the known limits in the Americas. But the experimental archaeology results in their attempt to falsify the hypothesis appears solid and there are some cultural lithics to support it. It may, however, come down to whether or not these lithics are convincing since so many stone tools from extreme suggested ages have characteristics in common with geofacts.

Alaska, 1840 BP

Another recently discovered footprint, while not nearly as old as its Chilean counterpart, may be just as fascinating.

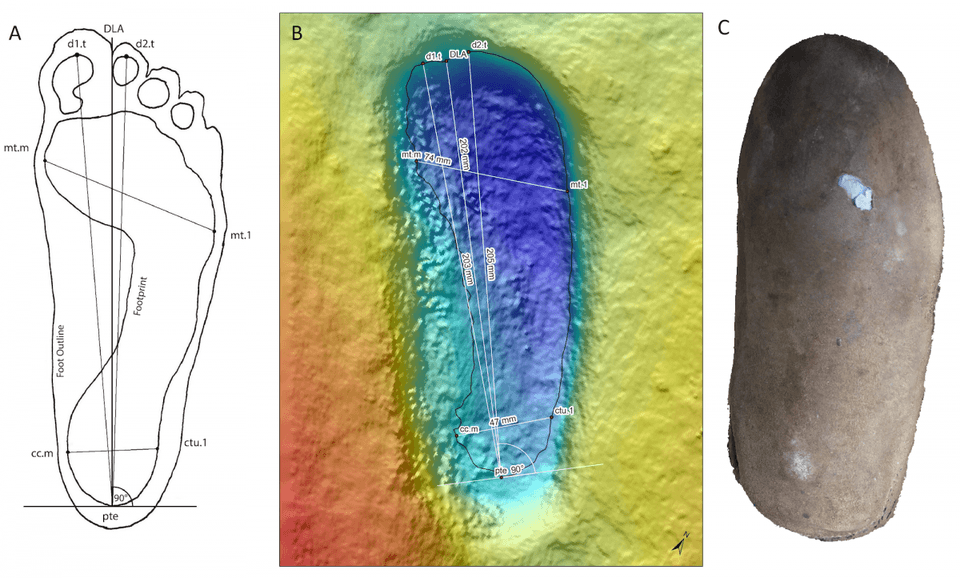

At the Swan Point site in central Alaska, researchers from the University of Alaska and the Alaska Museum of the North describe a right footprint of a “healthy, non-obese 9-12-year-old child” wearing some sort of footwear or shoe.

The footprint itself was found in context with the floor of a pit house about 6 km northeast of the Tanana River in central Alaska. The Shaw Creek Flats of that area are “broadly characterized as a black-spruce bog interspersed with small lakes, creeks, and stands of birch, with the current vegetative regime holding stable throughout the middle Holocene.”

Excavations in this region have been on-going since at least 1991 and seven prehistoric cultural components in four Cultural Zones along with one historic component have been identified. Earliest occupation in this region of Alaska goes back at least 6000 cal years.

The pit house and the footprint age, however, is closer to 1840 cal BP based on the 2005 excavation results of a housepit in the same stratum.

Certainly the age isn’t to be as controversial an issue as the Chilean print. But what makes this find interesting is that it’s an example of the first subarctic print of its kind described from Alaska. And the presence of children and subadults in the archaeological record is extremely low, especially when you consider that children may be as much as one-third or more of any given population.

Further Reading

Moreno, Karen; J. E. Bostelmann, C. Macías, X. Navarro-Harris, R. De Pol-Holz, M. Pino (2019). A late Pleistocene human footprint from the Pilauco archaeological site, northern Patagonia, Chile. PLOS ONE, 14(4), e0213572.

Smith, G.M., T. Parsons, R.P. Harrod, C.E. Holmes, J.D. Reuther, and B.A. Potter (2019). A track in the Tanana: Forensic analysis of a Late Holocene footprint from central Alaska. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 24, 900-912.

Carl, would the much lower presence of children’s footprints be down to the fact that infants would be carried and younger children would be be much lighter in weight, have much smaller feet and hence, leave us with very few distinguishable prints today?

I doubt it. As soon as a child is capable of walking in modern hunter-gatherer cultures, they’re expected to use their own mobility. We have to be careful applying modern expectations to cultures in deep time, however. But I can’t imagine there would be a lot of difference. Also, we just have so few examples of human footprints in antiquity at all. Of the millions and millions of people that came before today, only a handful of fossilized footprints exist in the entire world.

What’s astonishing, however, is just finding evidence of children in the archaeological record. This is something that is rare in itself. Or is it? My thought is that many times we find things that are left behind because of non-adults but we misidentify them. Probably not a lot, but perhaps some things like figurines, rock art, lithics (particularly those that were failed attempts to create a culturally relevant style), and so on. I suppose, in a way, these things are only partially misidentified. We’re just not acknowledging that they belong to children, but scientifically, this just isn’t possible. At this time, anyway.

So, when archaeologists *are* able to see children in the archaeological record, it’s pretty special.

I would imagine that an person ‘growing up’ in hunter-gatherer cultures would find that childhood is very short and as you say, mobility would be expected quickly to enable them to survive. As a parent I would also assume that children of ancient times made the best of what they could find lying around to play with, I know with my young daughter; that if you take her to the country side without toys, footballs Etc, she will be quite happy playing with sticks and stones.

I would also suggest that maybe animals in a pet roll played a part in their childhood?

Childhood in deep time would be nothing like we see today.