Back in September, a paper published in the journal Science Advances concluded that humans might have settled, or at least visited, Madagascar about 6,000 years earlier than previously thought.

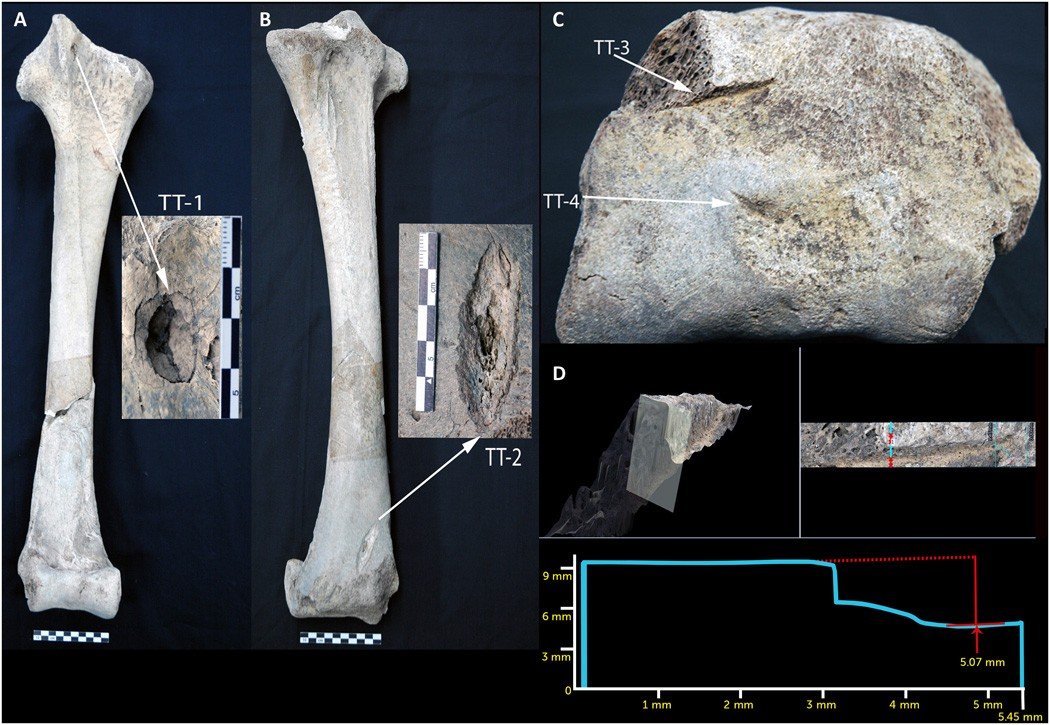

The team led by the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) examined the ancient bones of Aepyornis and Mullerornis, extinct elephant birds, and claimed they showed evidence of cut marks and depression fractions from hunting and butchery practices. This, they said, put prehistoric humans on the island at around 10,500 years ago.

Prior to that announcement, it was thought that humans arrived at around 2,400-4,000 years ago. This former assumption was based on artifacts and lemur bones with similar cut marks and fractures.

A Controversial Claim

A little more than a week later, the quarterly science magazine, Cosmos, quoted archaeologists who took issue with the ZSL conclusions. One stated that “there’s not a lot of other evidence to support this finding” and that it was “a leap too far” to conclude the presence of humans at 10,500 years ago.

A Contradicting Study

So, today, when PLOS ONE published, “New evidence of megafaunal bone damage indicates late colonization of Madagascar,” it came as no real surprise.

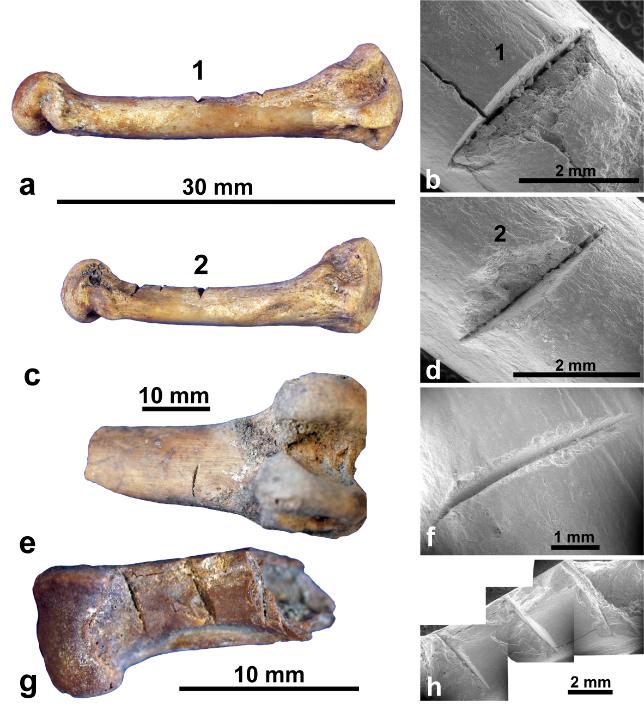

Anderson et al analyzed 1787 bones of extinct megafauna ( hippos, crocodiles, lemurs, tortoises, and elephant birds) from Madagascar dating to between 1900 – 1100 years BP. What they found was that in all bones with potential cut marks and butchery marks that dated prior to 1200 BP, microscopic analysis of the marks showed that they were not made by ancient humans. Some were gnaw or bite marks of other animals, some were root etching, some where even “chop marks from excavation.”

Only after 1200 years BP did the potential cut marks show themselves to be made by human tools.

And they also re-examined previously collected bones that were identified as having human cut marks under the microscope. The same held true with these bones.

The authors found that their analysis is consistent with other data from diverse lines of evidence—”bone damage, palaeoecology, genomic and linguistic history, archaeology, introduced biota and seafaring capability”—which, together, suggest human arrival on the island we know today as Madagascar later than 1350-1100 years BP.

It might be interesting to note that Anderson et al., did not do their study in response to Hansford et al. In fact, this later research was accepted at PLOS ONE in May of 2018, four months prior to Hansford et al. I mention this since it was concurrent research. It would be interesting to see the Anderson et al. methods applied to the Hansford et al. specimens.

I’m not an expert on zoological analysis and identifying cut or butchery marks. But both sets of authors, working at about the same time, used microscopy to analyse ancient megafaunal remains from Madagascar. Hansford et al. concluded that their bones dating to about 10,500 years BP had cut marks; Anderson et al. concluded that many potential cut marked bones prior to about 1200 years BP really weren’t.

Who’s right?

My money is on Anderson et al. but I’d really like Hansford et al. to be right. Human arrival at Madagascar that early would be exciting and have technological implications that would be fun to explore (i.e. boats since Madagascar is over 1700 km from the mainland of Africa).

Sources and Further Reading?

Anderson A, Clark G, Haberle S, Higham T, Nowak-Kemp M, Prendergast A, et al. (2018). New evidence of megafaunal bone damage indicates late colonization of Madagascar. PLoS ONE 13(10): e0204368. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204368

Hansford J, Wright, P, Rasoamiaramanana A, Perez, V, et al (2018). Early Holocene human presence in Madagascar evidenced by exploitation of avian megafauna. Science Advances, 4(9), DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aat6925. http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/9/eaat6925

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.