On their website today, the banner with the words, “1818-2018 momento de união e de reconstuir” (1818-2018 a time of union and rebuilding) takes on a new meaning. Also on the webpage for the national museum is the notice that they are in mourning due to the fire that ravaged the building along with nearly 20 million objects on September 2, 2018.

The Museu Nacional de Brasil was one of the largest museums in the Americas for natural history and anthropology and it was the oldest scientific institution in Brazil. Founded in 1818 by King John VI of Portugal, it housed over 20 million objects of the natural sciences and anthropology–not just for Brazil–but for the world.

Its Pre-Columbian collections from throughout the Americas was extensive, but so were those of Egypt and the Mediterranean. In addition, the museum held one of the largest scientific libraries on the continent with over 470,000 volumes that included over 2,400 rare works.

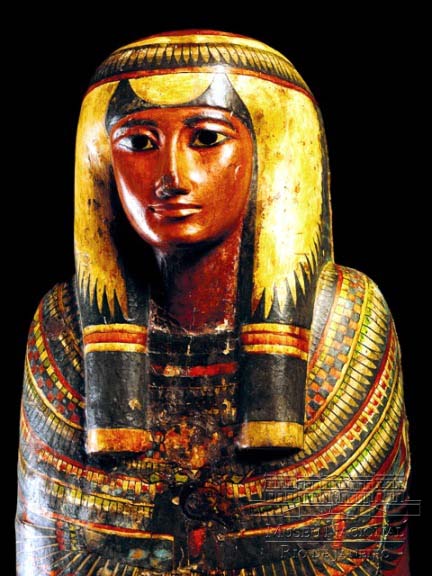

Sarcophagus of Sha-amun-en-su. Photo by Dornicke

Mummy “Princess Kherima.” Photo by Dornicke

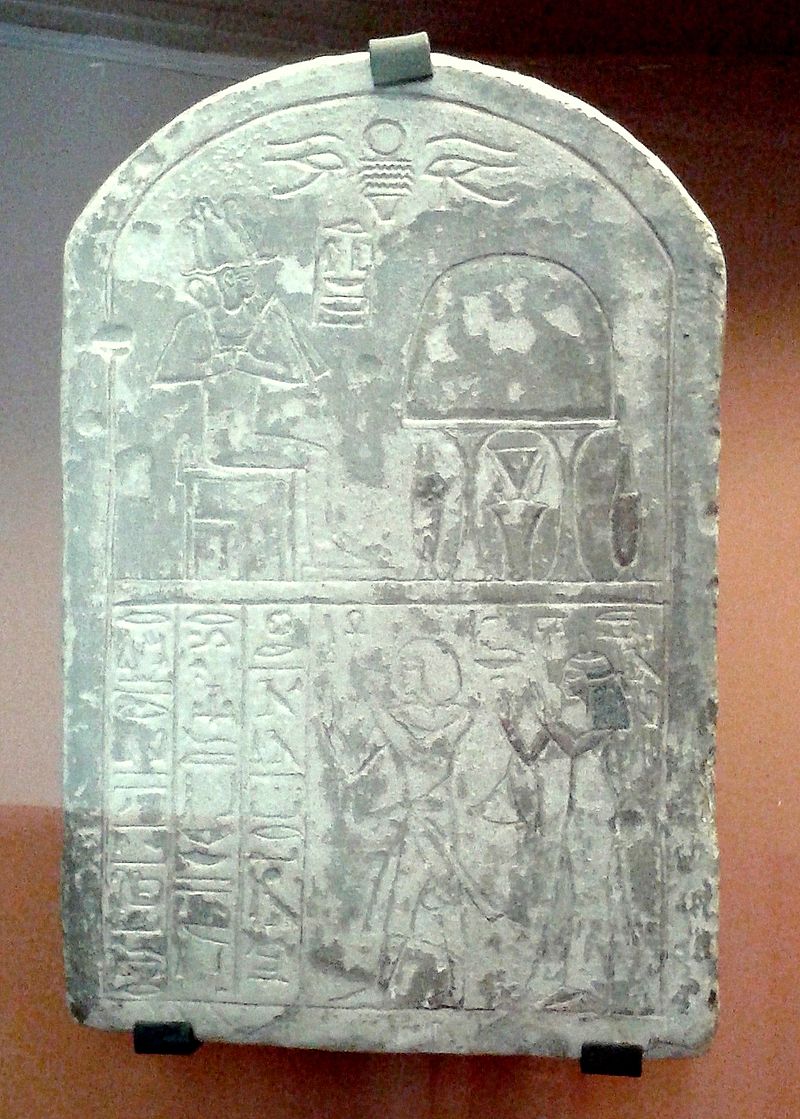

Stele of Raia. Photo by Dornicke

Photo by Celso Abreu

The Egyptian collection numbered more than 700 items and was considered the oldest and largest in Latin America. It included the sarcophagus and mummy of Sha-amun-en-su from the Third Intermediate Period (750 BCE), and the mummy commonly referred to as “Princess Kherima,” which dates to the Roman Period (1st-3rd centuries CE). In addition, there was the sarcophagus of Hori, also from the Third Intermediate Period (1049-1026 BCE); the Stele of Raia (New Kingdom, 1300-1200 BCE); a golden mask of the Ptolemaic Kingdom (~304 BCE); and a bronze figure of Amun.

Corinthian oinochoe. Photo by Dornicke

Red-figure krater. Photo by Dornicke

Alabaster Venus or Leda figure. Photo by Dornicke

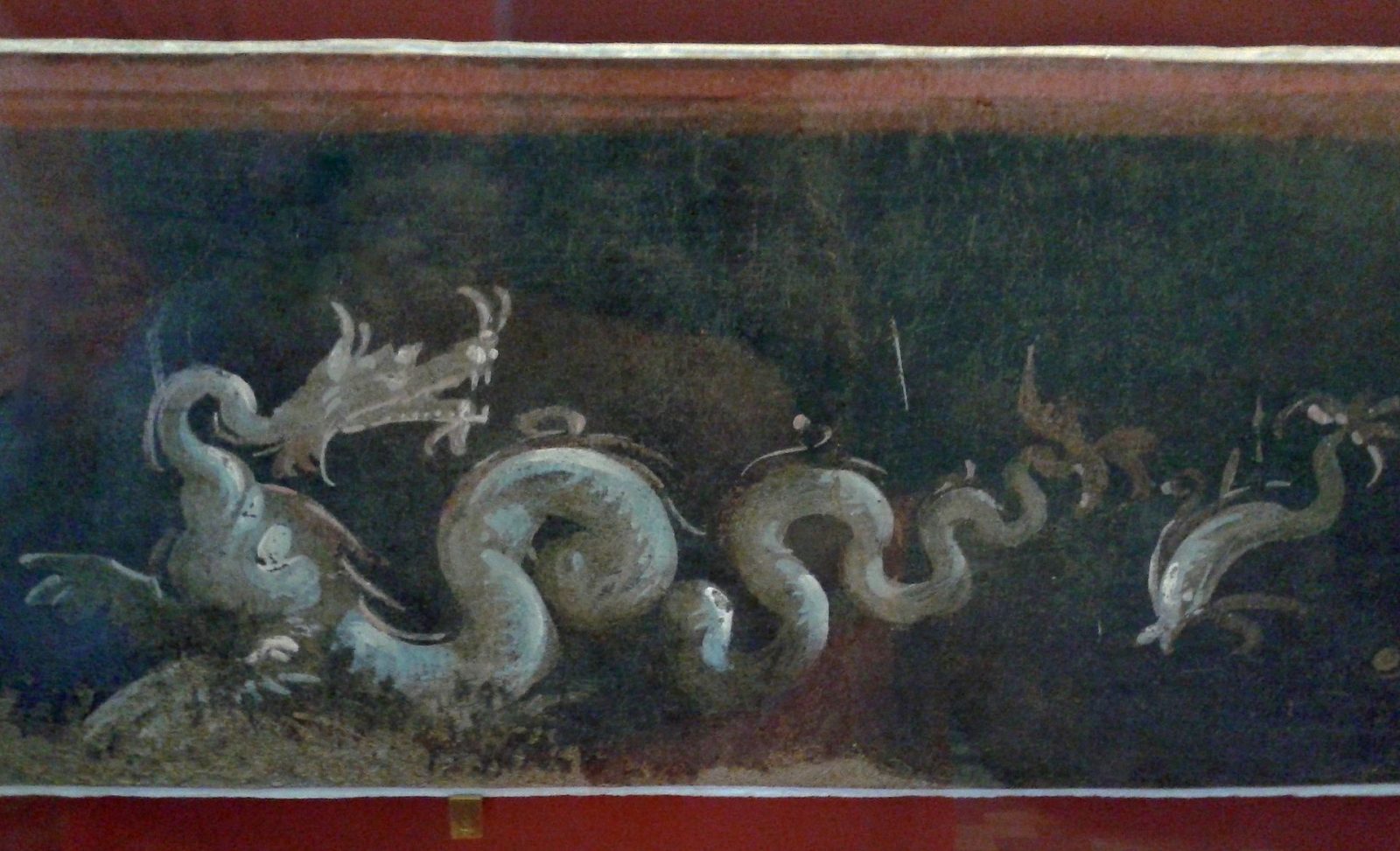

Fresco from the Temple of Isis. Photo by Dornicke

Highlights of the various items from Mediterranean cultures include a fresco from the Temple of Isis which represented a sea dragon and a dolphin (1st century CE); a Corinthian oinochoe (wine jug) with its lid (600-575 BCE); a Campanian (Italy) red-figure krater (4th century BCE); and an alabaster figure of Venus or Leda of Hellenistic times.

Photo by Celso Abreu

Photo by Celso Abreu

Photo by Celso Abreu

Photo by Celso Abreu

Photo by Celso Abreu

Photo by Celso Abreu

Wari figure. Photo by Dornicke.

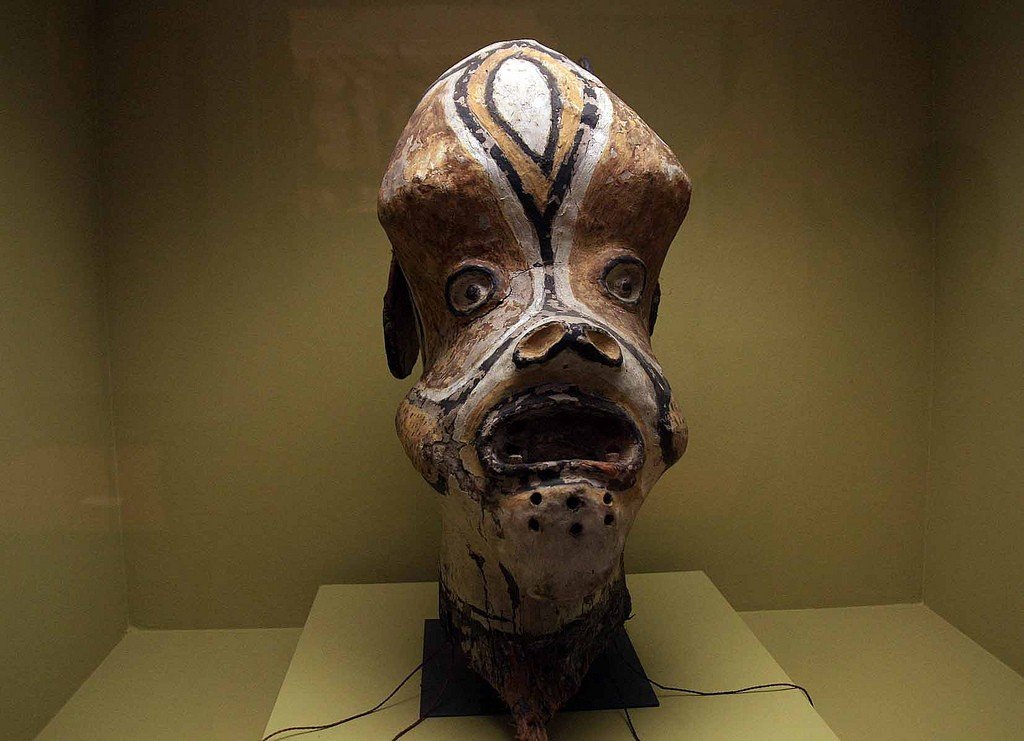

Jivoroan culture shrunken head. Photo by Dornicke

Photo by Celso Abreu

Photo by Celso Abreu

Chancay culture textile. Photo by Dornicke

The Pre-Columbian collection, however, was perhaps a particular source of pride for the museum. Artifacts of indigenous cultures throughout the Americas during the Pre-Columbian era were housed at the Museum. These included objects from:

- Nazca culture (~1st century BCE – 800 CE Peru)

- Moche civilization (~8th century CE Peru),

- Wari culture (~5th century CE Andes),

- Lambayeque culture (~8th century CE Peru),

- Chimu culture (~10th century CE Peru)

- Chancay culture (~1000-1470 CE Peru)

- Inca civilization (~13th century CE)

The photos above highlight only a few of the millions of artifacts, books, displays, and other objects that were lost in the fire which took over 80 firemen from 12 barracks across the city of Rio de Janeiro until 2 am Monday morning to control.

The Fire and the Building Itself

The fire began in Saint Christopher’s Palace (Paço de São Cristóvão), after closing, and controlling it was hampered by a lack of water in the fire hydrants near the building. Eventually, water was obtained by piping it from nearby lake water.

In addition, lack of funding made improvements to the infrastructure of the mansion the museum operated in an impossibility. Once the residence of the Portuguese Royal Family, the structure was well over 200 years old and an historic site itself since 1938.

Installation of a fire suppression system for the Palace reportedly would have cost over $5 million (21 million BRL) and talks to fund it were apparently under way between the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES) as the National Museum began its 200th year celebration.

The Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) operated the museum and its rector, Roberto Leher, was reported to say,

This is a very old building that was conceived in a context where there was no use of energy, how we use academic buildings. We have laboratories, administrative areas, computers that have great energy use,” Leher said. The restoration, he said, provided for the installation of a very robust fire prevention system. UFRJ, like other Brazilian universities, is living today in a context of a lot of budget constraints, and of course in this context all areas of the university are affected.

Also, the director of the museum, Alexander Kellner, apparently warned of the Palace’s precarious conditions in May, before the bicentenary celebrations.

There’s no word on how many, but some of the items in the Museu Nacional were either rescued or survived the fire. Almost certainly Bendegó meteorite survived. It survived a fall to Earth and didn’t burn up in the atmosphere only to be melted in a fire. And I found at least one photograph of a firefighter or museum staff member carrying out an object. We can assume other objects may also have been rescued.

A firefighter rescues items during a fire at the National Museum of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil September 2, 2018. REUTERS/Ricardo Moraes

Bendegó meteorite. Photo by Jorge Andrade

What Now?

A fire like this raises lots of questions and lots of concerns. And rightly so. How can such a tragedy be prevented elsewhere? That is the question that should be foremost on the minds of those in charge of or responsible for collections elsewhere in the world.

And they don’t have to be in a 200+ year old palace with antiquated wiring to be at risk. Fire management plans are designed to save lives, not collections. Human life is the first and foremost consideration, otherwise it would be a simple matter of installing some sort of halon gas system in any building, which removes the oxygen from the air, choking the fire out. Unfortunately, this has the same effect on humans.

So some combination of approaches seems a wise choice. Including digital archives of collections.

Already, there are calls for anyone who has photographs of the collections from visits to email them to students at Uni Rio (the Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro).

For those wanting to prepare for something like the tragedy that hit this museum over the labor day weekend, many options at varied levels of archiving exist. From simple photographs to many photographs each object which could allow a 3-dimensional recreation of the object using a process called photogrammetry or structure from motion. Essentially a point cloud of thousands or even millions of points are computer generated by the combination of photos, which are then used to create the fill.

Such an endeavor can be expensive, as the software and the computing power are not cheap or insignificant. But, had the photographs already been taken and stored digitally, the items could be reproduced one at a time or as needed. And equipment needed to record and store the photographs is cheap. It’s the cost of a decent camera and hard drive space to store it on.

Other methods include 3D scanning using tripod mounted lasers or handheld scanners. These can be pricey solutions, but what price can be put on losing objects for good? There are books, texts, and artifacts lost in the Museu Nacional fire of 2018 that will never be studied. There are probably some that were never even photographed a single time.

Sources:

Amorim, Paulo Henrique (2018). Museu Nacional: Golpe destrói a memória do Brasil. Conversa Afiada.

Truly awful its so frustrating when this could have been prevented by some funding. It’s nice to think that items could be re-produced but that’s like displaying tourist souvenirs compared to the original collections.