Like any good stories of adventure and intrigue that involve archaeology, this one begins with a treasure map!

Once upon a time, I happened to be rummaging through an old drawer full of historic photos and documents while recording an historic site for the Forest Service when I happened upon a folded map of our Forest with two photocopied pages of a legal pad sandwiched inside. The map was like many I’d seen before: a black and white USGS topographic map of the regions our Forest sits in. But there was something curious about this one. There were a few dozen, maybe a hundred or so, small circles with a number and a letter inside—each with short line pointing to a location on the map.

The first thing I noticed was each location seemed to be at a spring or very near a creek. Then I looked at the two photocopied pages. The was a partial list that corresponded to some of the numbers. Twenty-one through twenty-five, with several letters as a sub-section under each. Next to each of these were short descriptions.

One read, “barrel hoops, jugs.” Another simply said, “55-gal drums, galvanized vats, jugs.” The others were similarly annotated.

It occurred to me that what I had here was a partial list of moonshine still locations. The map and the list were in a set of files kept by the Tennessee Valley Authority when they managed the region beginning in the 1960s through the end of the last millennium. Ages ago. The map was ancient. Okay, maybe not ancient.

I set this map aside and actually forgot about it for some time. The locations weren’t going anywhere and the map key was incomplete, plus I had other work that needed doing.

Then, one day an apprentice working in our trails department handed me a bunch of legal pad sheets that were stapled together, numbered 1-30, each number with 2-6 lettered subsections. Each of these described vats, jugs, barrel hoops, cisterns, and other still related artifacts and features. It was the completed key!

So we set out to see what was there.

Wait, before I take you on that journey, you’ll want to know a little about moonshine stills. This region in Western Kentucky and Tennessee has long been known for moonshine, the illegal distillation of organic material into alcohol for consumption. It’s made from corn, sugar, fruits, etc. During the prohibition era, folks around here were in need of money to get by. It was also the depression era. But the government was actively working against these surreptitious and covert manufacturers of alcohol.

I’ve interviewed many local descendants of these manufacturers and sometimes they seem proud of their moonshine roots; other times they seem a bit less so. But nearly all agree that since it was to be done, Golden Pond moonshine was going to be done right. It was going to be a quality product. One not rushed. Not confused with radiator rot-gut.

One thing that seems unique in the hardware of this region is the use of the square or rectangular vat. Take a look at his drawing:

Apparently, rectangular vats in this region were favored because they could be made and transported in the back of a pickup truck, but still make maximum use of space. If you put a round vat in a pickup truck bed, you end up with a diameter as wide as your bed. If you use a rectangular vat, you can get more gallons per cubic foot.

So, armed with knowing what it took to produce moonshine (barrels for fermenting the mash, a cooker, jugs to put it in for transportation, concrete blocks to raise the cooker for a fire below, a spring or water source, etc.), we set out to see what might remain of some still locations.

At the first site we checked, we found a 55-gallon drum, a bit of pipe, and possibly the coolest thing we probably could have found (short of a dozen or so unopened jugs of aged-shine): a galvanized, rectangular vat!

The vat we found was nearly pressed flat by its own weight over time, being exposed to the elements for decades. But you could still easily discern the dimensions (roughly 2.5′ x 3′ x 2′). It was made of lightweight galvanized metal with soldiered corners and joints. A copper handle was soldered to one end, perhaps to aid in lifting the lid or moving the vat.

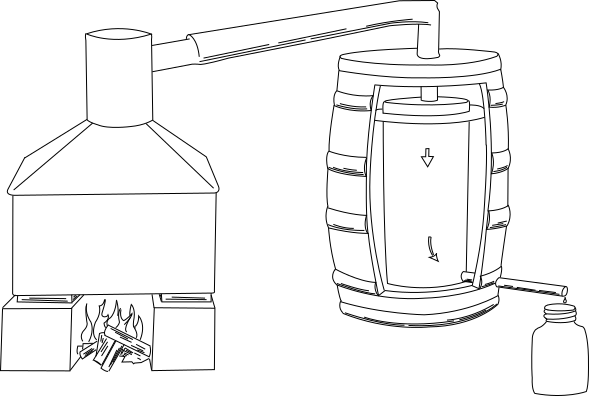

The 55-gallon drum would probably have been used to ferment mash, which would probably have been corn, sugar, and yeast. From this, and after a few days of fermentation, alcohol is produced by boiling the mash in the cooker. Alcohol boils faster than water, so the steam that makes its way from the cooker, through the gooseneck pipe, to the cooler, which in a barrel of water, goes back to liquid as moonshine. I suspect if we go back with a leaf blower, we’ll find other artifacts like broken jugs and barrel hoops.

At the second site we visited, we found only the remnants of a cistern, but this site was very close to an active forest service road. The first site was a fair hike from any road. The third, not too close to the road, but not terribly hard to get too, produced a barrel hoop and the bottom of a 1-gallon glass jug. And it was very near an active, spring-fed creek.

The barrel hoops seem to be the thing most described in the map key. Within the information from local informants about moonshine in the Golden Pond area of Kentucky are descriptions of wooden barrels for aging the alcohol and giving it the brown tint of whiskey. This is done in oak barrels that are charred from the inside.

As archaeology of sites like this goes, the first step is to do pedestrian survey of suspected locations, record what artifacts or features are visible. Then follow up with more detailed surveys. Perhaps we pick a few to come back with a leaf-blower, maybe we come back after a controlled burn. Possibly we could run a metal detector survey, pin-flagging hits, then excavate a small unit that encompasses a concentration of hits.

I’m very interested in seeing how many vats are still present on the landscape, particularly the rectangular variety.

We’re only just beginning what will probably be years of data collection and research into the story of moonshine production in this region. But it’s a story, good or bad, that’s part of the history in the region that deserves telling.

And understanding.

Better than the old metal drums I used to find in the woods in my area – those were just hazardous waste from local factories.