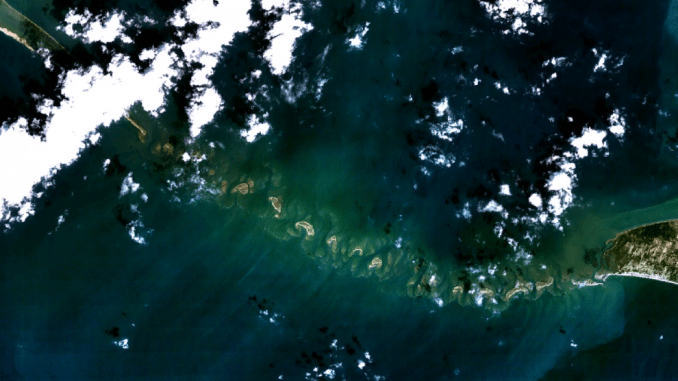

Between India and Sri Lanka is a thin strip of land that stretches from Pamban Island in India to Mannar Island in Sri Lanka. It’s known by several names: Adam’s Bridge, the Rama Setu, Rama’s Bridge, and Ramar Palam. And it has been a source of contention among the people of India and, perhaps to a lesser degree, the people of Sri Lanka.

India has several major ports for oceanic trade, two of the largest being the Jawaharlal Nehru Port near Mumbai and Chennai port. The first is in the Arabian Sea, the second in the Bay of Bengal. Any shipping from one side of India to the other means sailing around Sri Lanka. As early as the 18th century, those eager to shorten the shipping routes between East and West Asia, proposed a canal that joins the Palk Straight in the north with the Gulf of Mannar in the south.

Since the 1990s, several attempts have been made to fund the Sethusamudram Shipping Canal Project, a massive undertaking of grand proportions that would dredge a deep-water canal up to 50 miles long in the Sethusamudram–the sea that separates Sri Lanka from India which is bisected by a narrow tombolo of land. While mostly comprised of sand, deposited over thousands if not millions of years, perhaps over a block-faulted ridge between Sri Lanka and the mainland, the Rama Setu is seen by many as a religiously and culturally significant site.

The Ramayana tells us the story of a bridge being created by Hanuman’s monkey army at the behest of Lord Rama over 1 million years ago. He needed the bridge in order to cross the sea into Sri Lanka and rescue his wife, Seti, who is kidnapped by the demon-lord Ravana while Rama is out hunting. Confronted by the sea as he set out to rescue her, he threatens to shoot the ocean with an arrow from his bow, but the ocean convinces him that there’s a better way: a bridge can be built by Hanuman’s monkey army so Lord Rama may cross with his army. The bridge is built, Lord Rama crosses and engages Lord Ravana in a great battle, ultimately defeats Ravana, then rescues Seti, then returns with her across the bridge.

One need not be a believer in the story of Lord Rama and his daring rescue to recognize this strip of land has cultural and religious meaning.

Carl Saur, a geographer who was also possibly the first to describe and define what it means to call something a cultural landscape once said:

The Cultural Landscape is fashioned from a natural landscape by a culture group. Culture is the agent, the natural area the medium, the cultural landscape the result.

The Cultural Landscape is fashioned from a natural landscape by a culture group. Culture is the agent, the natural area the medium, the cultural landscape the result.

An option that I think would be worth considering for those interested in preserving Indian Cultural Heritage would be nominating the Rama Setu as a Unesco World Heritage Cultural Landscape. Within their guidelines, there are 3 categories of cultural landscapes:

- A Clearly defined landscape designed and created intentionally by man. “This embraces garden and parkland landscapes constructed for aesthetic reasons which are often (but not always) associated with religious or other monumental buildings and ensembles.”

- An organically evolved landscape. “This results from an initial social, economic, administrative, and/or religious imperative and has developed its present form by association with and in response to its natural environment. Such landscapes reflect that process of evolution in their form and component features.” These can be either a relict or fossil landscape in which the cultural process ended but is still visible; or a continuing landscape that is still evolving culturally but distinctly.

- An associative cultural landscape. Justified by “virtue of the powerful religious, artistic or cultural associations of the natural element rather than material cultural evidence, which may be insignificant or absent.”

A few years ago, I wrote an article for Culture and History Digital Journal that explored the Sethusamudram Project and its place in public culture since the 1990s through now. If you’re interested in the details of how it played out in the media and what some of the economic and environmental arguments and objections are in addition to the obvious religious ones, follow the link to my paper below. I warn you, it’s a pretty boring paper overall, but you can skip to the relative sections and get the data you need if you’re interested.

Further Reading

Feagans, Carl T. (2014). Sacred, Secular, and Ecological Discourses: the Sethusamudram Project. Culture & History Digital Journal 3(1), DOI:10.3989/chdj.2014.009.

Sauer, Carl O. (1963). “The Morphology of Landscape” , in Landand Life: A Selection from the writings of Carl Ortwin Sauer, ed. by J. Leighly. Berkeley: University of California Press, 315-350.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.