Crossing the Sands of Time: an Examination of the History and Legends of the Great Uighur Empire.

Jack E. Churchward

Paperback: 206 pages

ISBN-10: 1733056602

Paperback: $14.95

Kindle: $9.99

Today, Uighurs (pronounced WEE-gurz) are considered one of 55 officially recognized ethnic minorities in China and, although China rejects the idea that they are an indigenous group, they have a rich history in Inner Asia. This area is more commonly thought of as Central Asia and includes Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, and occasionally Afghanistan and Turkey. Since about the 10th century or so, Islam has been an important part of the Uighur culture and this is likely a contributing factor the significant oppression of their culture by the People’s Republic of China. Thousands of Uighurs today are being “re-educated” and forced to renounce their culture by the Chinese government.

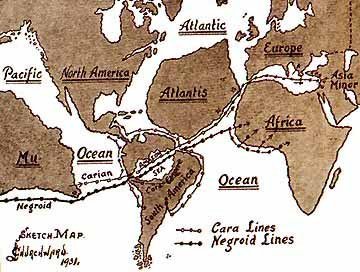

In Crossing the Sands of Time, Jack Churchward tells a unique story centered around the Uighurs of Central Asia. It’s a story of the past but one that includes a bit of psuedoarchaeology and pseudohistory as perhaps originated by his great-grandfather, James Churchward. The younger Churchward, an electrical engineer by trade, has also made it his purpose to research the life and theories of the elder, and share this with others. Jack’s great-grandfather, James, happens to be the writer of a series of books on the lost continent of Mu, which was the home of a civilization that suffered a set of cataclysmic events, sinking beneath the sea but not before birthing the human race.

The book is short, but informative. Particularly if the reader is unfamiliar with Uighur (also spelled “Uyghur” but I’ll stick to the spelling on the book cover for consistency) culture. The first four chapters outline Uighur history beginning with a geographic description of Inner Asia along with a brief over-view of the peoples present in this region from the Paleolithic through to the pre-Uighur Khaganates of the 6th Century CE.

The second chapter provides a fairly detailed timeline of the Great Uighur Empire from the mid-6th Century CE to around the middle of the 11th Century CE.

In chapter three, Churchward briefly describes the lasting affects the Great Uighur Empire had on Inner Asia including the spread of Islam among the Uighur people and their migrations throughout Inner Asia and the Tarim Basin in particular.

In the final chapter of Part 1, Churchward reflects on the more recent notions of Uighur culture and their modern identity as an ethnic minority. There’s also an essay by Erkin Alptekin, a Uighur activist living in Germany, addressing the question, “is Eastern Turkestan a Chinese Territory?” Alptekin also wrote the forward to the book.

If Part 1 of the book was the historical/factual section, interspersed with mentions of historic accounts and descriptions of archaeological assemblages of various sites, Part 2 is the section that dives into the alternative/fringe views that were originated in the 1920s by James Churchward, the author’s great-grandfather.

This section includes three chapters with the first being, “Tales, Legends, and Mysteries of Long-Forgotten Places.” In this first chapter of Part 2, the author describes his motivations for researching his great-grandfather’s work. While the younger Churchward doesn’t appear to overtly set out to debunk the elder’s claims, he also makes no attempt to defend them. He acknowledges that his great-grandfather’s ideas are contrary to factual data but, refreshingly, his interests lie more in discovering the elder Churchward’s motivations, meanings, and original intent.

The story line provided hope for a different future from the day-to-day realities of life under the ‘dictatorship of the people,’ the Chinese Communist Party. After decades of propaganda and prosecution for their unique heritage, the new mythos provided a sense of optimism and confidence in their identity.

Crossing the Sands of Time, Page 47

While the Lost Continent of Mu wasn’t new as a mythos—it’s been around since the 1920s—the Uighur translation of the text is relatively recent. And this line near the bottom of the page in this section of the book immediately grabbed my attention. I was eager to understand how an alleged continent that sank hundreds or thousands of years ago in the Pacific could possibly afford a sense of optimism and confidence to a modern ethnic minority about one-third the way around the planet and nearly a hundred years after it was written.

Jack Churchward didn’t disappoint. In the second chapter of Part 2, he outlines the elder Churchward’s apparent invention of Mu as a continent and a civilization along with their dispersal following a cataclysm. And he ties it all in with the Great Uighur Empire but at timelines that aren’t in line with the archaeological evidence. This chapter is a fascinating read into the origins of a myth that many are familiar with but few really know the details as they were originally presented much less how they came to be. Much of today’s pseudoarchaeological media being sold to consumers of cable television and books by authors like Graham Hancock have their origins with early adventurers who were left behind as archaeology morphed from a pastime to a profession. This chapter provides a wonderful inside track to that phenomenon.

Chapter 3 of Part 2, along with the previous chapter, is one of the longer, more detailed chapters. This one covers “Other Mentions of the Great Uighur Empire” in early fringe and alternative literature, such as the readings of Edgar Cayce as told by Shirley Andrews. Most of these writers have a connection to Mu or James Churchward and the younger Churchward does a good job of describing the depth and breadth of these associations and their relation to the Great Uighur Empire and Uighur culture.

The core of the book is only about 100 pages long with nearly another 100 pages dedicated to appendices that, for the most part, are valuable reprints of various texts from the 1920s through the 1930s that mention Uighurs and the Uighur Empire.

Jack Churchward makes a solid case that James Churchward’s early literary works which mention Mu and the Uighurs are escapist literature designed to help the average person in the West find a sense of hope or optimism during the Great Depression. Ironically, they may well have the same effect on modern Uighurs in need of that same hope and optimism in the face of ethnic genocide at the hands of the Chinese government.

If you’re curious about the Uighur people, their history, and their current plight, this book provides an excellent primer. If you’re curious about the origins of the legend of Mu and what motivated James Churchward to create it along with what effect it has had in the last 100 years, this book is an excellent source of information.

It’s a short book and a fast read, but the information is solid and concise. If you have an interest in either the Uighurs or the story of Mu, it’s worth the $14.95 price tag.

Further Reading

Buckley, Chris and Edward Wong (2019). Doubt Greets China’s Claim That Muslims Have Been Released From Camps. The New York Times, July 30, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/07/30/world/asia/china-xinjiang.html

Al Jazeera (2019). “Stain of the century”: US denounces China’s treatment of Uighurs. Al Jazeera, July 18, 2019. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/07/century-denounces-china-treatment-uighurs-190718134228281.html

Churchward’s first ravings about Mu pre-dated the Depression by several years, although he might have later been tapping into the escapism market (like plenty of other people) by the time that the Depression really got rolling.