In my last post, I discussed both the Old Babylonian and the Akkadian versions of the Gilgamesh Epic and some of their similarities and differences. I find the Akkadian acceptance and fascination of Sumerian gods and mythology to be fascinating itself. I often wonder if, perhaps, their fascination with the earlier Sumerian culture could be analogous to the fascination modern Americans have with Native American culture. Like the Akkadians, we assign many place-names based on Native words and we continue to have a special reverence for Native mythology and culture.

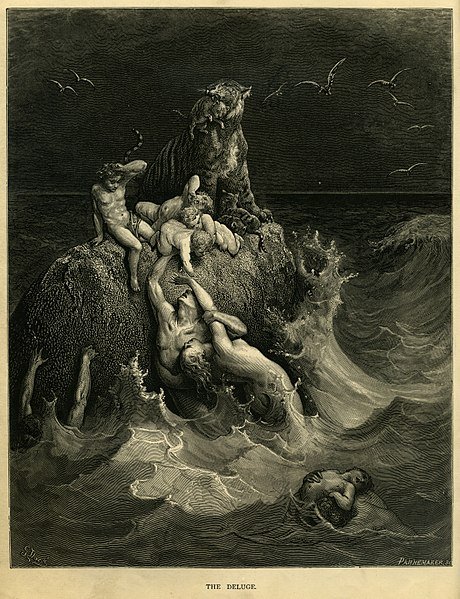

In this part, I’ll quote two passages of the Flood Myth present in Gilgamesh which demonstrates the popularity and appeal of at least one aspect of the story that still resonates with people even today.

PART II

Non-Mesopotamian versions of the Flood diverge further. Berossos, who wrote the Greek history of Babylonia in the 3rd century BCE, has his ark land in Armenia rather than Dilmun or even Mt. Nisir. He uses the name Xisouthros instead of Ut-napishtim, indicating that he is familiar with the Ziusudra version, but the use of mountains might demonstrate an embellishment designed to show that no culture could escape the flood. Nisir is only 9,000 feet and further south, while the Armenian mountains are probably among the highest known to Berossos. It could very well be that the original intent of the story was to maintain the Dilmun connection in an inaccessible and secret land, since NI?IRTU, the possible source of the NI SIR sign in line 140, means “inaccessible,” “secret” or “hidden.” The assumption that the sign referred to Nisir may have led to an embellishment of landing the boat on a mountain, further embellishing the significance of the Flood’s reach.

By the time the story has been adopted by Jewish authors in Genesis, many embellishments are added, such as significantly increasing the number of days of rain from six or seven to forty days and forty nights; changing the perspective to a monotheistic one; the inclusion of two of every animal; the size of the boat; and so on. Even the reason for the destruction of mankind is embellished, evolving from being noisy to being wicked. But the core framework of the Sumerian flood myth still remains:

Gligamesh XI, 145-54

When the seventh day arrived,

I sent forth and set free a dove.

The dove went forth but came back since no resting place was visible, she turned around.

Then I set forth a swallow

The swallow went forth but came back, since no resting place for it was visible, she turned around.

I then set free a raven. The raven went forth and, seeing that the waters had diminished, he eats, circles, caws, and turns not around.

Genesis 8:6-12

Then it came about at the end of forty days, that Noah opened the window of the ark which he had made;

and he sent out a raven, and it flew here and there until the water was dried up from the earth.

Then he sent out a dove from him, to see if the water was abated from the face of the land,

but the dove found no resting place for the sole of her foot, so she returned to him into the ark, for the water was on the surface of all the earth. Then he put out his hand and took her, and brought her into the ark to himself.

So he waited yet another seven days; and again he sent out the dove from the ark.

The dove came to him toward evening, and behold, in her beak was a freshly picked olive leaf. So Noah knew that the water was abated from the earth.

Then he waited yet another seven days, and sent out the dove; but she did not return to him again.

In addition to the similarities of the end of the survivor’s time at sea, other key elements remain, which include: deciding to send a flood to wipe out life on earth; selecting a worthy man to survive; building a boat; riding out the storm on the boat; offering a sacrifice on dry land at the end; and establishing a covenant between the gods and mankind. Ut-napishtim and his family achieve immortality and Noah is instructed to “be fruitful and multiply.” Ishtar tells Ut-napishtim that she “shall remember these days and forget never,” and Enlil, seeing the error of his rage, takes Ut-napishtim and his wife by the hands, touches their foreheads and announces, “Hitherto Ut-napishtim and his wife shall be like unto us gods.” Yahweh tells Noah, “I will never again curse the ground on account of man, for the intent of man’s heart is evil from his youth; and I will never again destroy every living thing, as I have done.”

In addition to the similarities of the end of the survivor’s time at sea, other key elements remain, which include: deciding to send a flood to wipe out life on earth; selecting a worthy man to survive; building a boat; riding out the storm on the boat; offering a sacrifice on dry land at the end; and establishing a covenant between the gods and mankind. Ut-napishtim and his family achieve immortality and Noah is instructed to “be fruitful and multiply.” Ishtar tells Ut-napishtim that she “shall remember these days and forget never,” and Enlil, seeing the error of his rage, takes Ut-napishtim and his wife by the hands, touches their foreheads and announces, “Hitherto Ut-napishtim and his wife shall be like unto us gods.” Yahweh tells Noah, “I will never again curse the ground on account of man, for the intent of man’s heart is evil from his youth; and I will never again destroy every living thing, as I have done.”

The natural appeal of Gilgamesh as an adventurous hero was likely a source of its popularity in pre-literate as well as post-literate Mesopotamia. Oral traditions may have out-weighed written ones in transmitting the story during the heights of Sumerian and Akkadian cultures, but the traces of the motif are present in cultures that are far removed from Mesopotamia in both space and time, testifying to the power of a good story to propagate itself in human culture, particularly when its themes of heroism, loss, survival, and friendship resonate so well with human nature.

References and Further Reading

Dalley, S. (1989). Myths from Mesopotamia: Creation, The Flood, Gilgamesh, and Others. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kraeling, Emil G (1947) Xisouthros, Deucalion and the Flood Traditions. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 67 (3), 177-183.

PSD (2006) Pennsylvania Sumerian Dictionary Project. Babylonian Section of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Anthropology and Archaeology. Found on the Internet at: http://psd.museum.upenn.edu/epsd/index.html

Pritchard, J. B. (1958). The Ancient Near East, Volume 1: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Woolley, C. L. (1928). The Sumerians. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.