A brief warning: this post contains a few images of sub-adult skeletal remains. The photos, however, are instructive and help to offer context.

I subscribe to a lot of archaeology-related Facebook pages. Mostly because I’m curious what others are saying about archaeology. Sometimes I engage the public as an archaeologist on those pages to help educate or bring archaeology to the interested lay-person. Other times I try to offer a rational, scientific perspective to the many pseudoscientific ideas floating out there on the interwebs.

Those interested in archaeology are easily moved by the mysterious and the fantastic. Some to greater extremes than others. In recent days, there has been a story going around the Facebook pages and groups regarding the recent find in Peru of 140 child sacrifices. The Archaeology Review Facebook page posted the National Geographic story on the day it came out.

The quick summary of the story is this:

Archaeologists in Peru excavated a site along the north coast of Peru that contained 140 burials of children and 200 young llamas, all of which appear to have been ritually sacrificed. This makes the site the location of the single, largest-known mass-child sacrifice in the world.

Most of the children were between the ages of 8 and 12 years old when they were killed. Textiles and rope found within the burials were radiocarbon dated to between 1400-1450 CE (between 568-618 years ago). Most of them were buried facing west, toward the sea. They each had cut marks on the sternum and ribs, an indication that their hearts were removed. Coupled with the red cinnabar pigment found on the faces of their mummified remains (naturally mummified due to the normally arid conditions of the region), and the evidence shows a mass, ritual sacrifice.

The llamas were buried facing east, and they were mostly under 18 months old. The east is the direction of the Andes mountains. The burials of 3 adults, 2 women and 1 man, were found close by. They each suffered blunt-force trauma to their heads—the likely cause of death—and had no grave goods. And they were probably killed around the same time as the children and llamas.

The site appears to be a single event, which the investigators could tell by the dried mud layer which was disturbed during the creation of burial pits and the sacrifice event itself. Footprints of sandaled adults and barefoot children along with those of dogs and the llamas were found in this mud layer. Some of the bodies of both the children and the llamas were left in the wet mud.

Facebook reactions

Some of the comments in various groups, as one might expect, were not very appreciative of the act of child sacrifice. In one, a commenter sarcastically said something to the effect of “I thought they were supposed to be peaceful hunter-gatherers.” In another group, a comparison to modern abortion clinics was made. Still another group’s commenter had generally unkind things to say about the entire Chimú culture, as if this were the defining aspect of everything they were. I’m sure there are other groups where the story was shared this week that had similar comments.

There’s no doubt that this would be considered an abhorrent act of violence in any modern context, Western or otherwise. And it’s probably not wrong to look at a past culture and find it a distastefully heinous thing to do, particularly to children.

But there’s also some value in looking at why the Chimú people thought this was a righteous course of action.

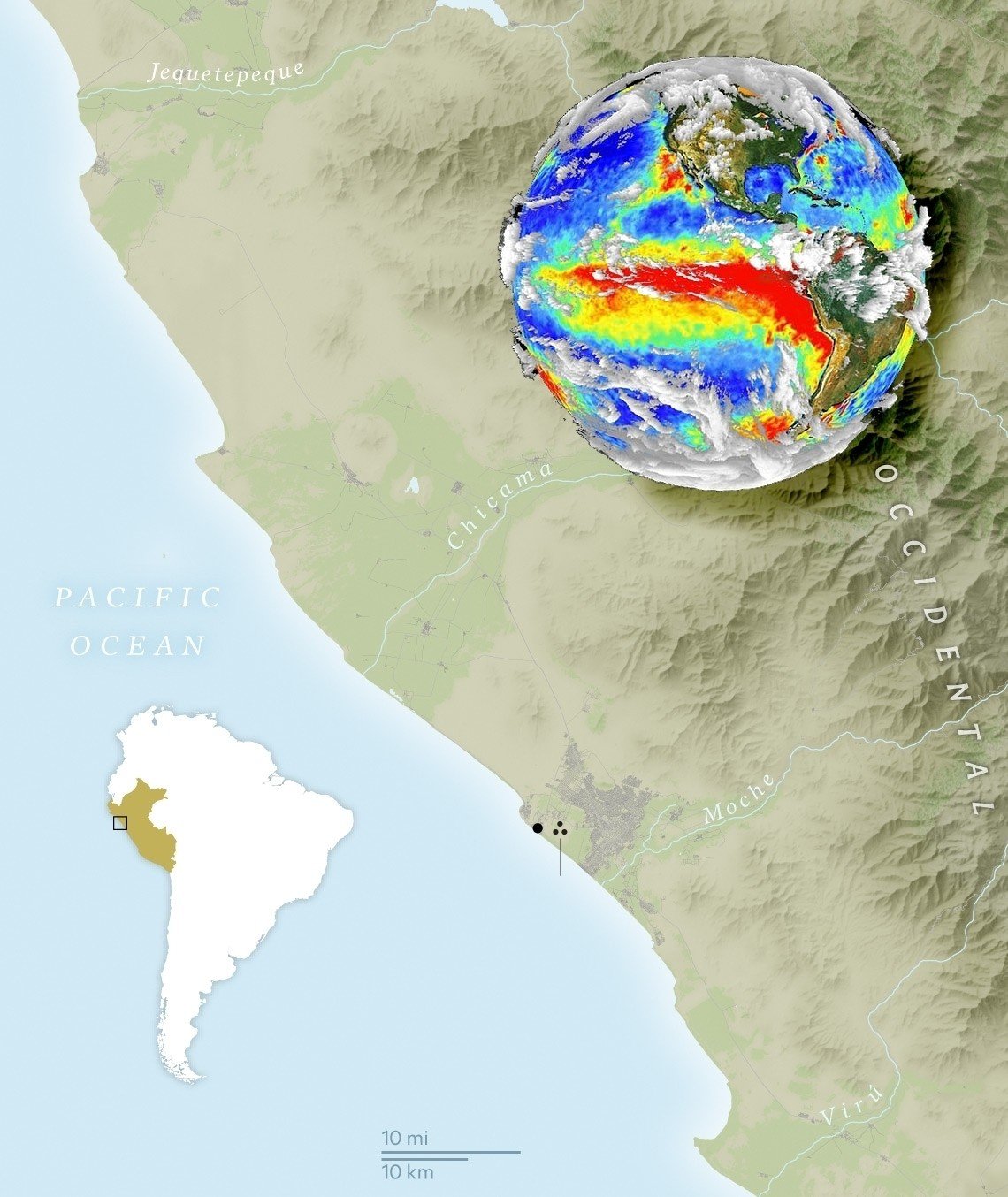

In the same period, between 1400-1450 CE, there is evidence that shows that an El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) event which actually peaked at around 1425 CE. In addition, the presence of the mud layer over the normal sand of the region is indicative of wide-scale flooding, a result of the torrential downpours that an ENSO event brings.

Which brings us to the why part.

Along with catastrophic flooding, which would have directly threatened lives, along with the filling of irrigation canals and devastation of crops and farmlands, the ENSO would also have significantly disrupted the fishing economy of the Chimú people who relied on both fishing and agriculture for subsistence. Their entire economy was based primarily around these two industries.

From their point of view, the gods were punishing them, angry at them, or—at the very least—lacking appeasement.

So they sacrificed to the gods.

But they probably didn’t go straight to 140 children and 200 young goats.

The term “sacrifice” in modern English comes from Latin and means to “make holy.” But, as a concept, it’s one that humans have used probably from the beginning. Over the millennia, long before history was written, humans have created god after god. Nearly all of them demanding sacrifice. And you can’t fool the gods (probably because you can’t fool yourself). It isn’t a sacrifice if you give up something that is meaningless. Abraham was willing to sacrifice his own son at an altar for Yahweh. The Aztec and the Maya mutilated their own tongues and genitals, offering the blood. They also cut the living hearts out of enemies or warriors. Throughout ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, servants and retainers were sacrificed with the death of rulers.

But not all religious sacrifices are the human kind. Modern religions routinely fast and have days of activity or dietary restriction. Non-religious people also sacrifice personal wealth, comfort, or status for their loved ones or simply for altruistic reasons. Some might find these sorts of personal sacrifices on a different level and not “holy,” but I think philosophically they represent the human ability to acknowledge there are worthy causes bigger than ourselves, be they supernatural or not.

The Chimú people very likely tried to appease the gods with small sacrifices. Then moved up to human adults. When that didn’t work, they may have arrived at the conclusion that they must give up something to the gods that was precious.

So, when you read the story National Geographic posted a few days ago, don’t read it thinking that the Chimú people viewed children as any less precious or valuable than we do. As a society, they were in dire straits. It may have been the case that children were already dying of disease, hunger, or even violent attack from the Inca, who finally subdued the Chimú in 1475 CE.

The unfortunate truth is that their clearly-wrong belief that human sacrifice of children would appease the gods may have also been reinforced by the fact that the ENSO event was in decline after 1425, based on coral studies nearby in the Pacific. So, from their point of view, the human sacrifice of children worked.

Further Reading:

Faddy-Vrouwe, Robert (2015). El Niño Southern Oscillation During The 15th Century: A Reconstruction From The Equatorial Central Pacific. BEnviSci Hons, School of Earth & Environmental Science, University of Wollongong,

Romey, Kristin (2018). Exclusive: Ancient Mass Child Sacrifice May Be World’s Largest. National Geographic Online.

I agree its’ disgusting to my modern sensibilities but then, so is a religion based on sacrificing one’s son to one’s self so…