In Fredericksburg, Virgina, on the corner of William and Charles, sits a concrete (or is it limestone?) cylinder. Perhaps less than 2 feet tall, maybe 1 foot in diameter, and with a “bench” cut out of it, the block was once used for the auction of human beings to other human beings.

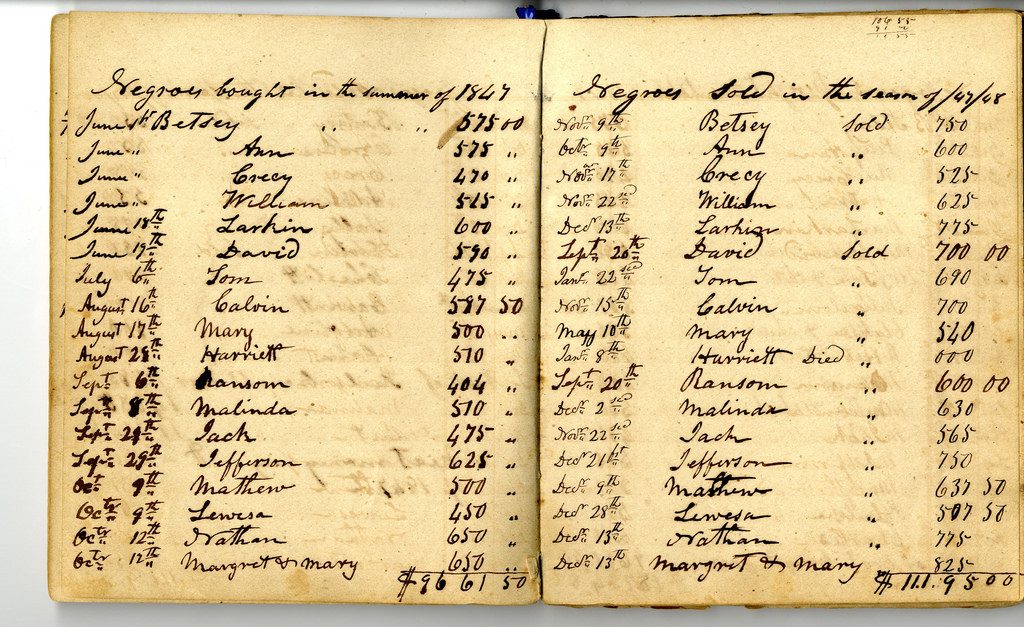

Through this auction block, families in the early to mid-1800s were broken up, children sold off from their mothers and fathers, husbands and wives separated for a few dollars, never to see each other again. The anguish, heartbreak, and total suppression of humanity was the purpose of this block.

Today, the block resides on the northwest corner of somewhat trendy shopping district, just outside the Olde Towne Butcher and catercorner from an Italian restaurant. A small plaque reads “principle auction site in Pre-Civil War days for slaves and property.”

For many, this is a stark reminder of a terrible period in our nation’s past when we once considered human beings of a certain skin color as livestock to be traded, sold, auctioned. For others it’s an abstract concept where they, as tourists climb on and pretend to have mock-auctions as they pass by. Or take selfies with it, which might be worse because, though a mock-auction is tasteless, at least it demonstrates they at least somewhat understand the block’s significance. Even if they fail to empathize with the lives destroyed here.

One would hope for a modicum of dignity, but many people are simply ignorant of the true depth of our nation’s past with regard to its relationship with slavery. A relationship that was so deep that it took a 4-year long civil war that cost nearly a million lives to finally abolish it. The racial bigotry and resentment still persists.

Recently, several archaeology groups have come to discuss this block, in particular whether or not it should be removed or left in place. The two general schools of thought are 1) it should be left in place since we shouldn’t be so eager to whitewash our past; we should be reminded of it so as not to repeat it. 2) it should be removed since it represents hatred and oppression and (some have said) “if we’re removing Confederate monuments this should go too.”

It should be quickly noted, however, that the Fredericksburg Slave Block is not comparable to the Confederate monuments. At least not in the way critics have attempted. The slave block is an actual, historic artifact of the period. The vast majority of the monuments commemorating the Confederate States were erected in the 20th century as a racist response of intimidation toward those pursuing civil rights for black Americans.

An informative article was recently published by The Guardian, which I recommend reading. The title includes a bias toward removal, but ultimately the say on whether the slave block remains or goes is up to the descendant population of the community. Above all others, they should be the primary consulted entity.

Let me clarify. What if the descendant population (blacks and whites) feel that this is an important part of their past, however abhorrent. One that should never be forgotten so as to never be repeated. And the slave block represents this moment in time that should not be whitewashed or glossed over. Perhaps they see it much the same way Jews see the gates of Dachau and it’s Path of Remembrance. A piece of physical evidence that one group of humans were able to dehumanize and so marginalize another to the point that they were herded and treated like livestock. The block, left in its original place, evidence of a terrible time in history in hopes that people of the present and of the future will never forget the terrible depths of behavior we are capable of to one another.

That was my first thought of the artifact. I suspect that’s yours as well. But let me flip this on its head a bit.

What if the descendant community (especially the blacks) perceive this as not part of history and as an artifact of the past but, rather, as an icon of the present? Left in place by a ruling white, privileged class as a reminder of how they view blacks in their community? What if the underprivileged see this artifact as a reminder of their lack of privilege? As an omen of their continued struggle to be accepted as an equal and legitimate voice within their own community? What if, unlike the Holocaust where the gates of Dachau represent a past never to be repeated, this slave block only represents an ongoing oppression that, while greatly diminished, is still far from over?

I don’t pretend to know what the people of the community think about this artifact. Maybe it’s neither of these things. But I also don’t pretend I have the right to decide for them. It’s their community. All I know is that I’d like the racial divide that allowed for the enslavement of my fellow human beings to be in the past, even if it isn’t as yet.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.