Edit (2/24/2019): I made an error and used the word “Ubaid” where I should have used “Uruk” for the period 3500-3100 BCE. This was a gross oversight that I should have caught by properly proof-reading my work. The inconsistency was pointed out by a commenter below, to whom I appreciate.

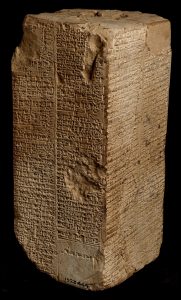

This one got under my skin tonight. There’s a couple fantastic claims about the number of years 8 Sumerian Kings ruled based on the mythical sections of WB 444, a cuneiform prism considered to be the best preserved kings list.

The claim is that there existed a culture of Sumerians and lineage of 8 kings for over 240,000 years, based on a list of kings written by the Sumerians.

This claim is interesting and, it might seem logical to accept the written words of the culture that wrote its own list of rulers until we dig a little deeper.

First, the list used in the article above (and for another article linked in this group with the same claim) is dated to the Intermediate Bronze Age (roughly 2100 – 1550 BCE). This tablet is actually referred to as a cuneiform prism though it has rectangular sides and reflects what is commonly referred to as the antediluvian set of kings–eight in all–as having a reign of 241,200 years. There are other kings lists that reflect differences. WB 62, for instance, lists ten antediluvian kings for 456,000 years. The Berossus tablet lists a different ten kings but for 432,000 years.

The post-flood lists are fairly accurate and match each other fairly well and are largely supported by archaeological evidence. But none of these kings lists are accurate for their “antediluvian” (also called “pre-flood”) dynasties. This is for several reasons:

1) The culture occupying the region which would later become that of the Sumerian culture (Ur, Uruk, and Eridu among a few others) was the Jemdat Nasr. A very separate and earlier culture from the Sumerian in many ways, but might be the ancestor culture of Sumerians. They had writing. Their texts dealt with administrative details, mostly to do with counting livestock and resources. None listed kings.

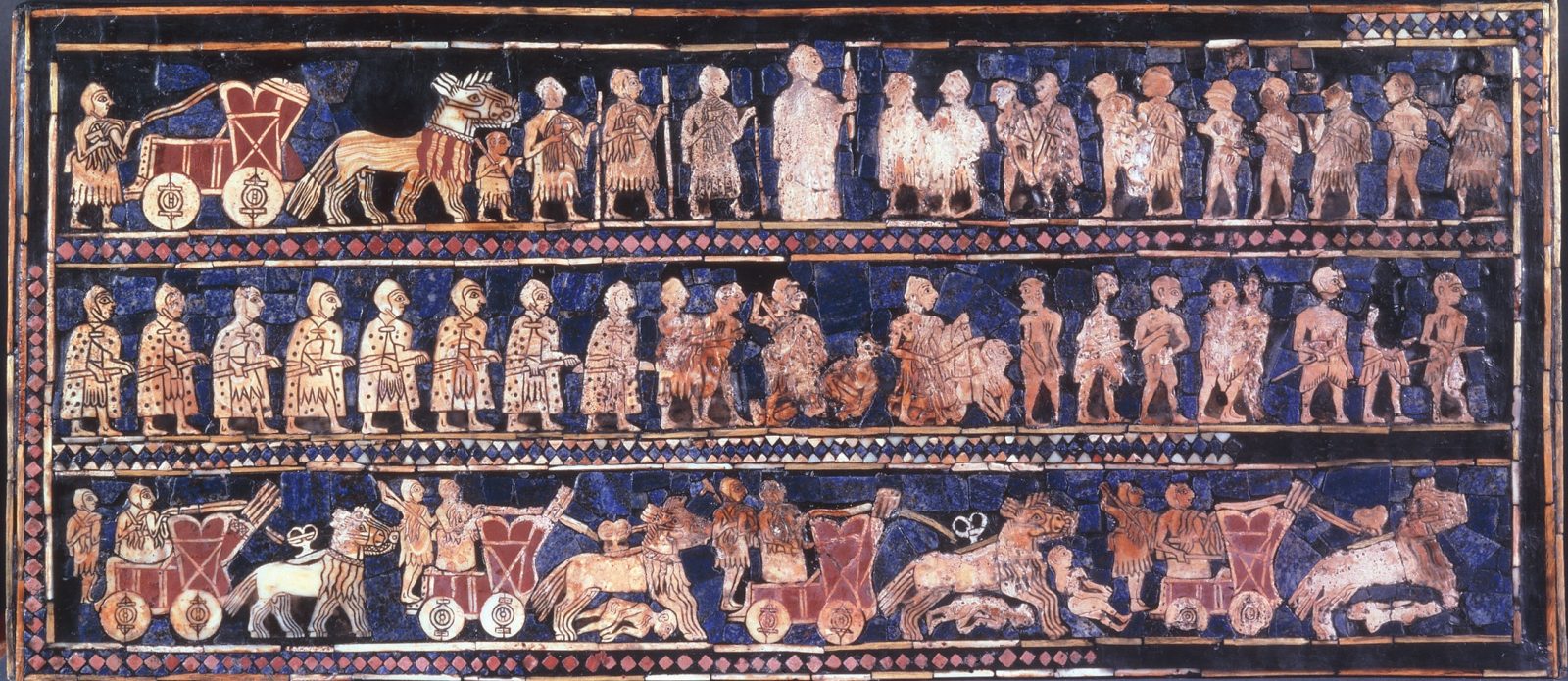

Prior to the Jemdet Nasr (3100-2900 BCE) were the Uruk (3500-3100 BCE) and the even earlier Ubaid (~5000-3500 BCE) periods. These two periods were less developed than the Jemdet Nasr though the Uruk period marked the beginning of the city-state. Archaeologically, evidence shows several cities like Ur were up to a kilometer square each, populated by as many as 20,000 people. This number grew in the Jemdet Nasr period and peaked to probably about 50,000 during the last Sumerian dynasty.

Digging deeper, the Uruk period (3500-3100 BCE) was where it all began for the urban sprawl that would eventually become Sumeria (2900-2300 BCE). In this period, archaeological evidence shows that egalitarianism is on the decline and stratification is on the rise. In short, agriculture and domestication of animals are becoming a primary subsistence strategy, making it possible for people to specialize in things skills ranging from basketry, weaving, and spinning to ceramic-making, brick-making, and metallurgy. Not everyone was needed to farm and raise animals. People started living in closer proximity and reed huts were giving way to mudbrick homes.

Evidence prior to this include the Chalcolithic and Neolithic, where copper and stone tools were the primary technology and nomadic, pre-agrarian bands subsisted off of seasonal plants and migrating animals.

2) The concept of “kings” and “dynasties” didn’t come around until populations grew, societies stratified (along with craft specialization comes elites who rule and prescribe religious practices).

3) The tablets that have these antediluvian sections of kings come from a period in which power and control was politically driven. The mythical sections helped solidify their power claims to regions by creating something “written in stone.”

4) People didn’t live longer in prehistory than they do now (archaeological remains show this to be factual, as do DNA/chemical analyses). In fact, the opposite is true: people in prehistory lived *shorter* lives than they do now for various reasons. There is no good reason to think that “kings” had longer life spans than modern H. sapiens and plenty of good reason to expect H. sapiens to fib a little for political gain. This last point is much, much easier to believe and requires fewer new assumptions.

5) Writing wasn’t invented until about 5,000 years ago. So how did anyone accurately store information for 195,000-236,000 years until what is comparatively just a few years ago when writing finally came about in that part of the world?

It’s been a while since I’ve read on Near Eastern archaeology, but it has always been an interest of mine. Please let me know if I left anything out or got anything wrong and I’ll update this. The idea is to have an alternative to the woo-claim that’s making it’s rounds out there on the web so that when well-meaning but less-informed (which isn’t a bad thing) people who have a genuine interest in antiquity look for the topic, maybe this will come up too and they can have a rational perspective.

References

LLoyd, Seton (1984). The Archaeology of Mesopotamia. London: Thames and Hudson.

Mellaart, James (1975). The Neolithic of the Near East. New York: Scribner

Postgate, J.N. (1992), Early Mesopotamia. Society and economy at the dawn of history, London: Routledge

Van De Mieroop, Marc (2004). A History of Ancient Near East: Ca. 3000-323 BC. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Wenke, Robert J. (1990). Patterns in Prehistory: Humankind’s First Three Million Years. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

You give to separate reigns of time for he ubaid period, 5000-3500bc and then a sentence later you have it at 3500-3100bc. Which is it? Also if all these lists are comprised from a single source wouldn’t it stand that the source is older? There is writing in the Danube river region going back to 6000bc so even the comment claim for the Sumerians inventing writing is a little off. It has also been shown that oral story tellers can keep knowledge alive over generations. It always amazes me how quickly scholars are quick to dismiss the stories of the actual people themselves. Even Troy was thought to be myth. I don’t believe that these antideluvian kings reigned the actual years attributed to them, but to dismiss them as fantasy is a little short sighted I believe.

You are absolutely correct in noting that inconsistency. One of those periods should not have been “Ubaid.” Instead, it should have read, “Uruk” and I’ve made the correction and added a small note to the top of the post to indicate it. Thanks again for pointing it out.

With regard to the question you posed: “if all these lists are comprised from a single source wouldn’t it stand that the source is older?” It certainly follows that if each of the lists (for example WB 62, which dates to about 2000 BCE and WB 444, which dates to about 1870 BCE) do have a separate, common source, the progenitor source would be older than these lists if even slightly. It may also be that the lists were comprised from oral tradition(s), which–also–would be expected to be older than, or at least as old as, the oldest list. Another option might be that the oldest list (i.e. WB 62) is the source list and differences on subsequent lists are due to political purposes.

There are a lot of things to consider, and they’d certainly be fun to explore (perhaps someone has or is). But they’re not all that relevant to the notion that there exist some extraordinary age to the Sumerian kings’ lists.

I’m comfortable standing by what I’ve said so far. The Vinca symbols, which date to about 5500 BCE (possibly slightly earlier for some) are very cool and intriguing–no doubt. But they’ve yet to be demonstrated as a system of writing. Most are found on pottery and a few figurines in the Neolithic of southeastern Europe, but they don’t seem to have a linguistic pattern that anyone has been able to discern as yet. My personal feeling is that many, maybe all, are representative of ontological ideas or concepts important to the people of the Vinca culture, but this isn’t something that I could ever demonstrate. Much the same can be said for the symbologies of Easter Island (Ronorongo script) and the Indus Valley (Indus script). Hopefully, someday, someone will discover a key to deciphering their meanings (assuming these meanings exist) and we can say confidently that the earliest form of writing is even earlier than we thought.

Finally, I’d point out that I didn’t simply dismiss the Sumerian kings list claims of extraordinary age out of hand. I detailed a handful of reasons why the notion wasn’t tenable. I even said, ” it might seem logical to accept the written words of the culture that wrote its own list of rulers until we dig a little deeper.”

There are probably a few other reasons why the Sumerian kings’ lists aren’t to be taken at face-value. Not the least of which is political propaganda. “Fake news” and invented histories aren’t exactly modern inventions! 🙂

So, it isn’t a matter of dismissing them as fantasy. They are fantasy. From there, the fun part of anthropology is to ask “why?” and “what are the implications?”