I’m the co-administrator of a couple of archaeology-related groups on Facebook and, in the last few days, I noticed several post submissions related to a recent online article about bioarchaeology and assigning gender to skeletal remains.

The article was hosted on a right-wing website that seems to cater to university-related topics, as long as they’re politically charged and divisive. At least for the most part. Search the article’s title, “Gender activists push to bar anthropologists from identifying human remains as ‘male’ or ‘female’,” if you really want to read it. But I’m going to address the main points of it here.

First things First

As you can see, the title is full of that loaded, politically charged rhetoric we’ve come to expect from click-bait sites and even the media in general. Particularly that Fox-News style designed to anger readers at the outset.

The “gender activist” the writer cites turns out to be an anthropology student on Twitter. I don’t know how many followers she originally had, but the post garnered over 4,000 shares, which really isn’t a lot by Twitter standards. I tried to look at the discussions and at least two-thirds of what I noticed were by the outraged, anti-woke crowd. The student has since made her Twitter account private, which was probably a good idea. I’m sure she’s getting all sorts of vile hate that shitheads on Twitter do best when they’re hurt or threatened in the feels.

So was this Twitter user (a.k.a. the “gender activist”) pushing to “bar anthropologists from identifying” the sex of human remains?

It didn’t seem that way to me. In fact, I got the sense what she was trying to say was that, regardless of how fuzzy the resolution is with identifying biological sex, bioarchaeologists specifically avoid making any determinations of gender, since gender just isn’t something that’s often represented in the physical remains.

I tried to find the rest of the Tweets in that thread, but I was a couple days late and the OP took her account private. Probably for good reason. The anti-woke/anti-trans crowd are generally complete assholes on Twitter and social media in general, particularly to women. But the fact that the right-wing article, the author of which found a random tweet of a random student to build outrage on, only quoted that introduction Tweet might be telling.

I suspect she was being taken out of context and the male writer couldn’t include screenshots of them and still perpetuate his invented outrage.

My guess is that she went on to explain some of the things I’m going to point out here.

Sex versus Gender

First, gender is not the same thing as sex. The latter refers to the biological capability of the individual’s body to potentially reproduce, specifically “a cluster of anatomical and physiological traits that include external genitalia, secondary sex characteristics, gonads, chromosomes, and hormones” (NIH 2022). And, as binary as that seems on the surface, sometimes it’s not so black and white, as I’ll discuss later.

Gender, however, is something different. This is what the ant-woke/anti-trans crowd often ignores. Gender refers to cultural and societal differences we apply to what it means to be a man or a woman. Where sex is male or female; gender is masculine and feminine. This is a notion that even the Supreme Court gets:

The word “gender” has acquired the new and useful connotation of cultural or attitudinal characteristics (as opposed to physical characteristics) distinctive to the sexes. that is to say, gender is to sex as feminine is to female and masculine is to male.

Justice Anton Scalia (1994). J.E.B v. Alabama, 114 S Ct., 1436

Because gender is so determined by culture, what it means to be masculine or feminine also vary greatly from one culture to the next. Men and women are different because they are taught to be different from the very moment of birth. In every culture. The differences in biology are minuscule compared to the differences we culturally assign.

And, as I write this, I realize that I’m still speaking in binary terms: male/female; masculine/feminine.

Not Always Binary Choices

The notion that there are opposing sexes or genders is, quite simply, wrong. And when it comes to sex, for every difference there are hundreds of similarities. Whether you’re male or female, we all share mostly the same biology. We can share organs, blood, catch the same diseases, digest the same foods, etc. Socially, we also want many of the same things: family, success, status, jobs, happiness, etc.

There very idea that there are only two sexes is also biologically incorrect, at least part of the time.

Size Matters?

The rate of intersexed—that is hermaphroditic—infants is probably far larger than the average person thinks. When a baby is born and their primary sex characteristics aren’t easily discerned, the decision to assign their sex was once often a matter of penis size.

While this practice is increasingly criticized, and may even no longer be common in the United States, the deciding factor had nothing to do with what many argue today as the “biological decider” of sex: the presence or absence of a Y chromosome. The doctors and surgeons simply assumed that no “male” would want to live life with a tiny dick. So they got to live life as a woman.

The National Institutes of Health outlines four categories of intersexed people, those people born with characteristics in sex development that do not conform to binary notions of male-female.

- XX intersex: A person with the chromosomes and ovaries of a woman, but with the external genitalia that appear male. (Usually the result of exposure to male hormones in utero or CAH). The person has a normal uterus, but the labia fuse and the clitoris is large and “penis-like.”

- XY intersex: A person with XY chromosomes, but with ambiguous or clearly female genitalia. Internally, testes may be absent, malformed, or normal. In the most famous cases of male pseudo-hermaphrodites in the Dominican Republic, this is caused by a specific deficiency in 5-alpha reductase. The child appears female until puberty, when their bodies are “transformed” into male.

- True gonadal intersex: A person with both ovarian and testicular tissue in one or both gonads. The cause of true gonadal intersexuality is unknown.

- Complex or undetermined intersex: Other chromosomal combinations, such as XXY, XXX, or XO (only one chromosome) can also result in ambiguous sex development.

From Kimmel (2011 p. 134).

The occurrence of intersex children described above might seem relatively infrequent, but it happens more than the average person thinks. According to Selma Witchel (2018), “the estimated frequency of genital ambiguity is reported to be in the range of 1:2000 – 1:4500.” Meaning that one of every few thousand people are born with intersex characteristics.

Odds are good that, by the time you’re an adult, you’ve come in close contact with an intersex person. A friend, a co-worker, a family member, a pastor, the person that delivers your mail… You might never know and they might not either. Feminizing and masculinizing surgeries at infancy are often performed to “normalize” the individual.

Let that sink in just a moment. For thousands of births each year, someone is deciding a infant’s gender. I won’t debate here whether this is right or wrong, there are a lot of good and bad arguments on both sides. The important take-away is that gender is not something that is biological—it is a cultural construct. A set of norms established by society.

Constructing Gender

Since gender is a social construction, Judith Butler (2006, pp. 10-11) asked a pointed set of questions about this. “If gender is constructed, could it be constructed differently, or does its constructedness imply some form of social determinism, foreclosing the possibility of agency and transformation? […] How and where does the construction of gender take place?”

In other words, since gender clearly isn’t constructed by biological sex, who get’s a say in defining what one’s gender is? Clearly societal norms play a heavy part. But to what extent is a person’s own agency—that ability to chose for them self—still part of the process? One has no agency at infancy, so that leaves parents and physicians.

If parents and physicians can chose a person’s gender, it stands to reason that gender can be decided by the individual at some point.

And this begins to bring us back to the point of the Tweet of contention: when identifying human remains of the past, it’s important—vital even—to not be so quick to assume that person’s gender. It isn’t just about picking the correct pronoun, which seems to send some snowflakes into meltdown. It’s about understanding that gender is not the same as sex.

Determining Biological Sex

To determine biological sex of skeletal remains, several techniques are commonly used, but the most reliable method is generally agreed to be hip bone analysis. Sexual dimorphism with this bone is a function of evolution: males evolved a pelvis for bipedal locomotion where as the female pelvis evolved with a compromise between locomotion and a need for childbirth, which requires sufficient space to pass a child’s head through the birth canal. Generally speaking, biological females have a round shape to their pelvis (gynecoid) and males have a heart-shaped pelvis (android).

Male (left) and female (right) pelvic bones. Photo from Wikicommons.

Thus, the male pelvis is generally more narrow than the female. Generally. The reliability is high, some sources saying at least 85% accurate with others citing 95% or better. Still, natural variation allows for departures from set norms within each sex. Also, there are metric and morphologic variations that can be expressed in the sexual dimorphisms between different ancestral populations.

The second-most reliable method, though significantly less reliable than pelvic analysis, is cranial assessment. There is a big HOWEVER attached to this method: sexual dimorphism of cranial features is very much dependent upon the ancestral or ethnic population of the individual being observed.

Essentially, the more robust features are consistent with a male skull and the more gracile features reflect a female skull. The most useful features are the nasal aperature, zygomatic extension, cheekbones, and supraorbital ridge. Also useful are the chin form, nuchal crest, mastoid process size, and mandibular symphysis along with a few others.

When looking at cranial remains that are at one end of the spectrum or the other, the decisioning is pretty straightforward. Most bioarch students see it right away. However, there’s a lot of overlap of normal ranges for each of these features between sexes. And sex dimophism varies significantly between different ancestral and ethnic populations. Sometimes sex determination just isn’t possible.

There are other methods of sex determination, but reliability is increasingly lower with these. Ultimately, sex determination is a best estimation given the available data. It is always possible that the examiner is wrong. But this is how science works.

Putting It All Together

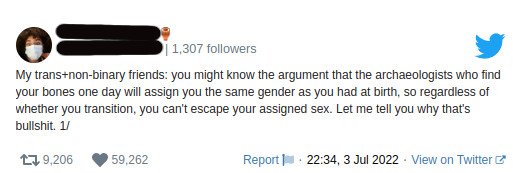

So, back to the student’s Tweet. She said:

My trans+non-binary friends: you might know the argument that the archaeologists who find your bones one day will assign you the same gender as you had at birth, so regardless of whether you transition, you can’t escape your assigned sex. Let me tell you why that’s bullshit. 1/

A Student’s Tweet from July 3, 2022.

Let’s break the Tweet down. Her audience was her trans and non-binary friends. Which is why she probably put her account on private after a conservative writer manufactured some outrage and outed her to the hoard of anti-woke/anti-trans nutters waiting for the next thing to spittle-shout at.

She then calls their attention to the argument that at least occasionally get’s made against their gender decisions, which is that “when you die, an archaeologist will find your bones and just assign your birth sex so your gender choices simply don’t matter anyway.”

If you followed me thus far, you already know some reasons why this is bullshit. There’s a fair chance that, even if your bones are looked at by an archaeologist, that they might not be able to be sexed. First, all the markers and features need to be present. Assuming that the bones are in good condition; assuming that archaeologists have any interest at all in you; they might still be wrong.

But lets assume these nosy archaeologists got it right with regard to your biological sex. That still says little about your gender. And we—archaeologists—are acutely aware of this. In his misogynistic ignorance, the writer of the article seems to me to have misrepresented what the student Tweeted. He said the student, “who is seeking an advanced degree in archaeology, called assigning gender to an ancient human ‘bullshit’.”

If you go back and actually read the Tweet, that isn’t at all what she said. What she said was bullshit was that her transgender and non-binary friends can’t escape their assigned sex.

We don’t know the reason(s) why this student was going to say it was bullshit, because the article’s writer didn’t include the rest of her Tweets. And now her account is private. Which is okay. We weren’t her audience and she took action to ensure only her audience could read what she had to say. Her prerogative and I respect it.

So let me share why it’s bullshit. Specifically that one cannot escape one’s assigned sex.

Mostly because it doesn’t really matter. Any archaeologist using methods of science to answer a research question knows that the biological sex is 1) a tentative estimate regardless of the percentage of accuracy, and 2) the gender cannot be assumed!

Just because we live in a society of high gender polarity does not mean we get to apply our own societal standards to the past. If you want to do scientific archaeology, this must be a consideration. Any archaeologist who ignores this is doing pseudoarchaeology.

If you read with me thus far, you know that there is a difference between sex and gender. And that there are people born every day that are considered intersexed. And that an intersex infant is often surgically altered so that there is a single sex that conforms to one gender or another. And, because of this, we can agree that gender is a cultural construct. We determine what it means to be male or female (pink/blue colors, dolls versus war toys, dresses versus pants, purses versus wallets, etc.).

How Many Genders Are There?

In the United States, gender is important. We’re largely gender-polar. We have bathrooms that are strictly for males/females. Sports teams are all-male; all-female. Clothing is rarely unisex. Even career traditions are only just now equalizing in the last few decades: nurses, flight attendants, doctors, CEOs of corporations…

There are, however, cultures where gender is not the central organizing principle of life. Both in the past and the present. It’s easy to assume that because there are two biological sexes that there must be only two genders. Right?

What about those four intersex categories? If we follow the one-for-one logic, those four plus strictly male and strictly female make six genders. Right?

Let’s agree that biological sex and gender needn’t be one-for-one.

In traditional Navajo culture, there are at least three accepted genders. The male and female you might expect, plus the nádleeh. One can be born a nádleeh or decide to be one.

“How,” you say, “can one be born a nádleeh?”

By being born intersex, of course. If a child is born and the sex is ambiguous, they’re considered a nádleeh. Or, if one wishes it later in life—if one feels the calling—one can become a nádleeh. The nádleeh performs the duties of both males and females, dressing as the gender for the task at hand. They’re free to marry either males or females. And there is so much more that a paragraph cannot describe.

Two-Spirits

Similar traditions are found in many Native and Indigenous American cultures such as the Crow and Lakota of the Plains and the Zuni of the southwest. European colonizers often called them berdache, but a more appropriate term, and more widely accepted from Canada to Mexico, is two-spirited.

The two-spirit gender is one comprised of those who live as both male and female. The ceremonial and social responsibilities and functions of two-spirit people differs somewhat from culture to culture as does the traditional name of this gender (batée for the Crow, wínkte for the Lakota, lhamana for the Zuni, and so on).

Very similar genders to the two-spirit are found in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific. In Mexico, there is a third gender called the muxe in Oaxaca, comprised of males who consider themselves to be more like females from a very early age.

It’s important to note that in all these cultures, with all these third genders, their communities no only accept them as individuals, but they are often relied upon socially. With the muxe, their communities “embrace them as especially gifted, artistic, and intelligent.”

Third and Alternate Genders in Archaeology

While much of the above is present within extant cultures or those of the recent past, there are also data that support alternative genders in antiquity. In my own research (Feagans 2014), which focused on clay figurines with anthropomorphic representations in the Mediterranean regions of Southeast Europe and Southwest Asia, I found that about half of the figurines of the Neolithic period were clearly female. Less than 2% were clearly male. And almost half were completely ambiguous. To the point of being intentionally ambiguous. All it took was the tiniest pinch of clay for the creator of these figures to express either female or male sex. Yet they did not.

This is not, by itself, instructive. No conclusion can be made. But questions can be asked: did the makers of figurines chose *not* to represent sex or gender in the clay, but leave it to the end-user to do so with clothing or other adornments? Like an anatomically blank doll, waiting for clothes? Did the ambiguous figures represent sub-adults? Did they represent a third (or fourth, fifth…) genders?

Bias and the Modern Lens

The data I collected in my master’s research sparked many more questions than these. But, whether or not the questions I had can ultimately be connected to ancient ideas of gender, I know I have to avoid the temptation to look at the past through the lens of modern gender assumptions. In general, all archaeologists understand this. In fact, the two-spirit gender of Native American cultures is a good reminder of how not to inadvertently colonize either past or present cultures.

For modern LGBTQ groups, the idea that a third gender exists now and in the past for so many indigenous cultures both in the Americas and southeast Asia was one quickly embraced. It had the potential to vindicate LGBTQ proponents who found themselves arguing against opponents who referred to transgendered and queer peoples as abominations.

But for indigenous peoples, the appropriation of a cultural past that Western LGBTQ have no connection with continues a colonizing tradition and erodes their sovereignty. And it obscures the nuance of diversity that exists with the two-spirit genders in various Native cultures.

Alternate Genders in the Archaeological Record

There are many, many examples where the evidence points to alternate or third genders present in the archaeological past. A corded ware burial near Prague, dated to between 2900 and 2500 BCE was that of a biological male buried in a position and with grave goods both associated with female burials. One of the archaeologists on the project commented that it was likely the interred person was “a different sexual orientation, homosexual or transsexual,” and the press of 2011 made a sensation of it, getting many things wrong and making many incorrect assumptions.

Luckily, some well-respected and vocal archaeologists were able to clarify the rational position of archaeology in general. How we should not only be careful to avoid looking at the data through a modern lens, using modern assumptions, but how we can’t even apply modern terms to the past. This will initially seem like more “wokeism” to some, but bear with me.

In today’s society, particularly in the United States, we see sexual orientation on very binary terms: straight and gay; heterosexual and homosexual. We also see gender on very binary terms: male and female.

This tends to force us into thinking of those who identify with another gender than they were born with as transgendered. The term “transgender,” is therefore a product of modern concepts of gender, which are traditionally male and female, and describe a person leaving one gender to identify with another. What if a person is raised from childhood in an alternate gender? They’re not really trans.

As we’ve seen among Indigenous Peoples of the Americas, binary gender isn’t a cultural assumption they begin with. In fact, most of the cultures that accept two-spirit genders have four understood genders; male, female, male-female, and female-male. In fact, among the Chukchi of Siberia, there are as many as seven recognized genders in addition to male and female.

As archaeologists, we should change our approach to the interpretation of past societies because our gender categories do not always correspond to those of a former reality.

Turek, J. (2016), p. 356.

We could agree, however, to use the term “transgender” as a shorthand for gender variance or atypicality, in periods of antiquity before the word was in use. This is something that has been argued by some scholars like Mary Weismantel (2013). Honestly, I think it would be fine as long as we’re in agreement that without data, we simply cannot assume the gender of an individual based on their skeletal remains even if we’re 95% sure of their biological sex. This applies to a person who’s been dead 5,000 years or just 5,000 hours.

We can only say what we know and deal with probabilities. And, in science, all conclusions are provisional and closest approximations of truth possible given the available evidence. Body position, grave goods, and adornments can all contribute to data used to explore an individual’s gender, but in the end, we don’t know how the individual identified. We can’t even assume that that gender identity is consistent with view of the individual’s family or society.

And now we see why it’s “bullshit” that archaeologists are in the practice of assigning genders. Whether it be the birth gender, birth sex, or something else.

There is much more to this topic than a blog article can possibly cover. Below, I’ve included some of the sources I discussed above so, if you have even the slightest interest in archaeology and gender, you’ll want to be familiar with them. What I left out of this article can probably be found in this list! I din’t even discuss the nature of homosexuality in ancient times, modern gender concepts like non-binary or gender fluidity or a hundred other “woke” ideas.

TL;DR No one is calling for a bar on sexing skeletal remains; bioarchaeologists already do not assume the gender of skeletal remains. Ultra-conservative snowflakes like to make each other melt with invented outrage.

Sources and Further Reading

Bruzek, J. and Murail, P (2006). “Methodology and Reliability of Sex Determination from the Skeleton”. In A. Schmitt, E. Cunha, & J. Pinheiro (Eds), Forensic Anthropology and Medicine (pp. 225-242). Humana Press. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-59745-099-7

Butler, Judith (2006). Gender Trouble : Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. New York. Taylor and Francis.

Feagans, Carl T (2013). A Study Of Anthropomorphic Figurines In The Neolithic Of Southwest Asia And Southeastern Europe (unpublished master’s thesis). University of Texas at Arlington.

Geller, Pamela (2019). “The Fallacy of the Transgender Skeleton.” In Jane E. Buikstra (Ed.), Bioarchaeologists Speak Out Deep Time Perspectives on Contemporary Issues, pp. 231-242. Springer Books.

Kimmel, Michael S (2011). The Gendered Society. New York. Oxford University Press.

NIH – National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2022). Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26424.

Turek, J. (2016). Sex, Transsexuality and Archaeological Perception of Gender Identities, Archaeologies, 12(3), 340-358.

Weismantel, Mary (2013). Towards a transgender archaeology: A queer rampage through prehistory. In S. Stryker & A. Aizura (Eds.), The transgender studies reader 2 (Vol. 2, pp. 319–334). New York: Routledge.

Witchel, Selma Feldman (2018). “Disorders of Sex Development”. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 48: 90–102.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.